"It’s been used more and more," but is Wisconsin's Len Bias law an effective deterrent to opioid abuse?

JEFFERSON COUNTY -- It is an epidemic that is sweeping the state, and the nation -- taking hundreds of lives every year, and it's only getting worse. As officials try to get a handle on the heroin crisis, many are relying on the courts to help send a clear message -- with tough prison sentences.

On a dreary, muggy day in Jefferson County, the feeling inside the courtroom was as heavy as the air outside.

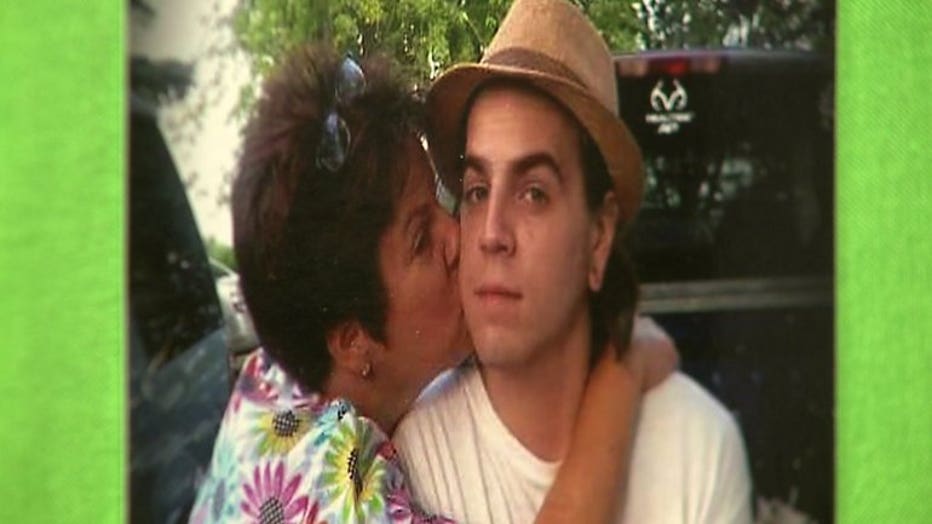

Lesa Treuden

“I’m going to ask the courts to sentence Samantha to the maximum sentence,” said Lesa Treuden, as she addressed the court. “This will never bring my son back, but hopefully it will spare other parents of their worst nightmare. Nobody wins here today -- nobody.”

Treuden shared her story with FOX6 News after losing her only son Dale earlier this year.

Dale died of a heroin overdose in July 2015. Dale’s death, unlike many others, resulted in an arrest -- his good friend Samantha Molkenthen, who was a heroin addict herself.

Dale Bjorklund

Dale Bjorklund

Samantha Molkenthen

Molkenthen was charged with first degree reckless homicide under Wisconsin’s "Len Bias" law.

The Len Bias law was put on the books in Wisconsin in 1988. It is named after the University of Maryland basketball star who overdosed on cocaine just two days after being drafted by the Boston Celtics in 1986.

Janine Geske

“It wasn’t used very often in the ‘80s,” said Janine Geske, a former Wisconsin Supreme Court Judge. “But I think through the years it’s been used more and more, and certainly now that we have this crisis of this heroin use prosecutors are looking to use it more.”

In the 28 years since the Len Bias law was passed in Wisconsin, most district attorneys in southeastern Wisconsin agree that it was rarely used until recently.

“I think they’re trying to use it more to try and discourage people from delivering drugs, “ said Geske.

Geske’s opinion is split when it comes to using the statute for criminal prosecution.

“I think the Len Bias law can serve a real purpose for people who are dealers, for people who are regularly selling drugs to people,” said Geske. “ I have more problem with it being used for a friend who shares the drug or who gives into a friend’s cry for relief at least at this point. I understand why it’s used, but I’m not sure if that’s the best approach."

John Chisholm

“When we go over 100 homicides per year, we’re deeply troubled and deeply concerned about it,” said Milwaukee County District Attorney John Chisholm. “Well, we’re tripling that with the overdose deaths.”

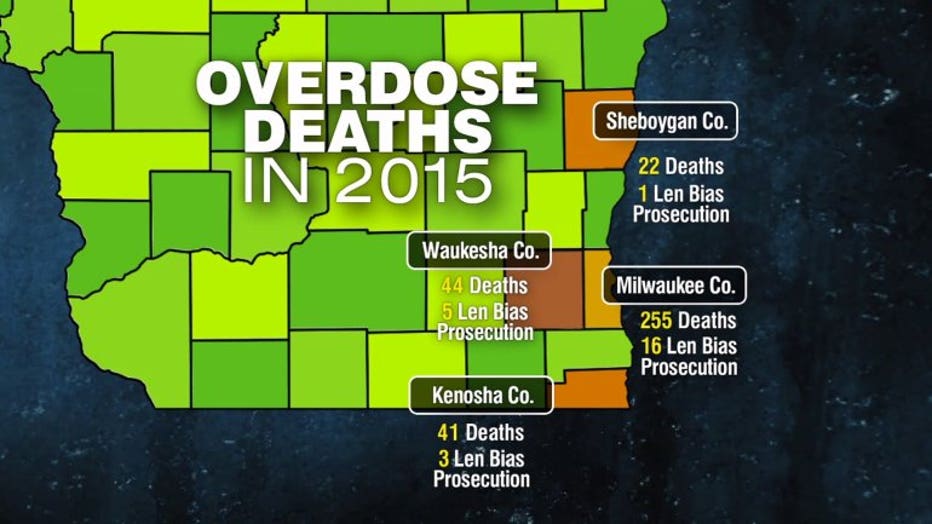

In Milwaukee County alone, there were 255 overdose deaths in 2015 with 16 of them resulting in prosecutions under Len Bias.

In Waukesha County, there were 44 overdose deaths in 2015, five of which resulted in charges.

There were 41 overdose deaths in Kenosha County in 2015 -- three cases were prosecuted under Len Bias.

Sheboygan County saw 22 overdose deaths in all of 2015 with just one case leading to charges under the Len Bias statute.

“Whether they sold it or not doesn’t matter under Wisconsin law,” said Sheboygan County District Attorney Joe DeCecco. “You just give it to them. You delivered it.”

Joe DeCecco

DeCecco said 2011 was the first time his office charged a person with first degree reckless homicide for delivery of a drug.

“A person died, so it doesn’t matter to me whether the person who delivered it is a fellow junkie, is a friend, didn’t sell it but actually gave it to them,” said DeCecco. “It doesn’t matter. A person died. What our object is is to get through the users and up to the suppliers.”

Samantha Molkenthen’s defense attorney Jonathan LaVoy said he understands the need for consequences, but believes all heroin homicide cases should not be looked at the same.

Jonathan LaVoy

“Samantha squarely falls into the category of a simple user,” said LaVoy. “She didn’t have any connections, didn’t even know the person they bought heroin from in Milwaukee.”

According to the criminal complaint, it was a series of text messages that connected Molkenthen to Dale’s overdose.

“There really wasn’t any cooperation here because she doesn’t really know anybody,” said LaVoy. “She was really just a daily user at that point and there really wasn’t much she could do to help herself.”

Samantha Molkenthen

“The whole purpose of the Len Bias law itself is to deter the drug traffickers themselves from engaging in the activity because of the danger it presented,” said Chisholm.

The question is, is it working?

Sue Opper

Waukesha County District Attorney Sue Opper said yes, but the deterrence message may be missing its intended target.

“The users are addicts themselves and they have very limited ability to react to the message,” said Opper. “I would say the drug dealers don’t care (because) they’re motivated by greed.”

“The deterrence in and of itself does not change the behavior as long as the incentive is too great,” explained Chisholm. “People are always focused on the short term, but it is our obligation to put priorities on what we value as a community and what we want to hold people accountable for.”

Because Molkenthen pleaded guilty to the first degree reckless homicide charge in Jefferson County, there was no trial.

Samantha Molkenthen

“The state is asking the court to impose a prison sentence in this case consisting of 15 years total time – 10 years initial, five years extended supervision,” Jefferson County Assistant District Attorney Jeff Shock told the judge.

“I believe a four to five year initial confinement sentence is appropriate,” said LaVoy.

In the end, the judge handed down a 15-year prison sentence for Molkenthen – nine years initial confinement, six years extended supervision.

“Sending a 20-year-old kid to prison for nine or 10 years isn’t going to solve anything,” explained LaVoy.

So what is the answer? If tough prison sentences and the deterrence message are not working, how does the state tackle this heroin epidemic and its broad deadly reach?

“I think there has to be other ways to do it,” said Geske. “This is not going to change the behavior of kids to the point that we are going to do away with the problem.”

Heroin

“There are many, many efforts underway to raise awareness, prevention, recovery treatment,” said Opper. “There’s many efforts, but to me I feel like we are treading water, I really do.”

Shock, the prosecuting attorney in the Molkenthen case did not want to be interviewed for this story, but did send a statement:

“This case is yet another example of the death and devastation that heroin is causing here in Jefferson County and throughout the entire state and country. Dale Bjorklund was a young man of promise who lost his life in large part because of the criminal conduct of the defendant. She knew the dangers of heroin because she had previously overdosed herself. And yet she still delivered the fatal dose to Dale. It is important that we hold offenders like Ms. Molkenthen accountable; and it is important that others who might think about following in her footsteps know that they are traveling down a path filled with death and imprisonment. We can’t prosecute our way out of this opioid crisis, but we can use the resources we have available to deter others from engaging in the conduct that ultimately resulted in the death of Dale Bjorklund. And if we do that, hopefully we can spare another family the devastation of losing a loved one to heroin. “