'Strangers believing in complete strangers:' Underground railroad conductor's descendant shares family story

Milton House Museum

MILTON -- Slavery is a dark reality of our nation's history. But, Wisconsin was a premiere anti-slavery state in the 1800s and a place in Milton, Wisconsin played a major role in that history. It is a history brought to life by a descendant of an underground railroad conductor.

The underground railroad offered an escaped to freedom. And, one of those stops on that journey was the hexagon-shaped Milton House, an inn that served as a stage-coach and railway hub. Think of it like a bus station with sleeping quarters.

Milton House Museum

Kari Klebba

"They took on a very perilous journey", said Kari Klebba, executive director of Milton House, which had an underground passageway that served as a temporary refuge for fugitive slaves between 1845 to the mid-1860s.

It's owner, Joseph Goodrich, was instrumental in secretly moving fugitive slaves in and out of his bustling inn. "And that's miraculous to me", said Klebba. "Strangers believing in complete strangers. A lot of faith."

Some of those runaway slaves were possibly transported by Vernum Hull, a pastor at Milton's Seventh Day Baptist Church, and the great, great-grandfather of Edna Dearborn of Racine. Hull was one of the Seventh Day Baptists of New York to follow Goodrich to Wisconsin.

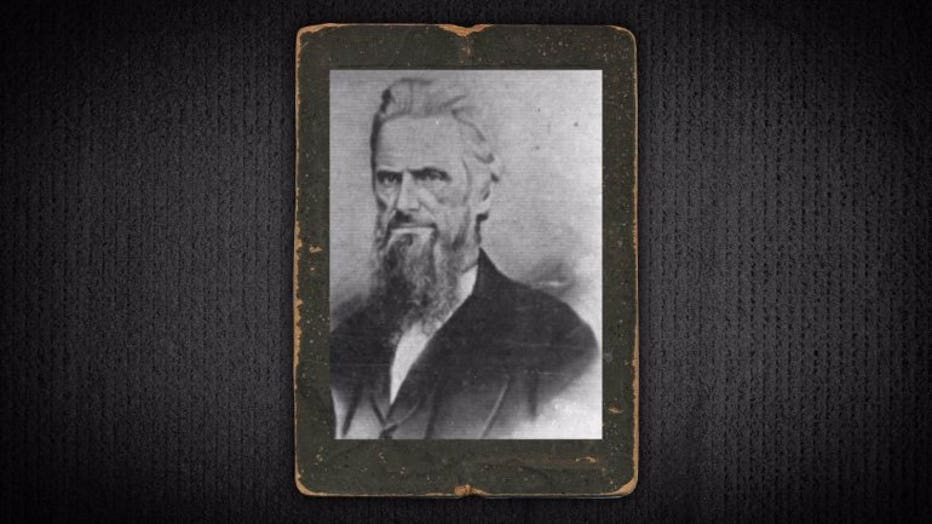

Vernum Hull

"My great-grandmother used to tell me these stories," said Dearborn. Her great-grandmother was Jennie Climena Mudge, Hull's daughter. "She was a tiny lady. She had a good sense of humor. She was peppery. There was nothing mild or meek about her."

Edna Dearborn

90-year-old Dearborn says Mudge was about nine or ten when she would accompany her father, an underground railroad conductor, on the wagon nine miles from Albion, Wisconsin to Milton, not far from the Rock River.

Edna Dearborn

"...behind the Milton House, wait until it was dark at night and then the slaves would be brought up and put in the wagon and they would be covered with potatoes," Dearborn said.

"And, potatoes make sense", said Klebba, "because we know the entrance into the underground railroad of Milton House was through a kitchen. So it would make sense that a big cart of potatoes would be sitting outside of that door."

"... and then they would be taken back up to Albion", Dearborn remembers her great-grandmother telling her. The next stop for the men and women seeking freedom was likely Racine, a port city.

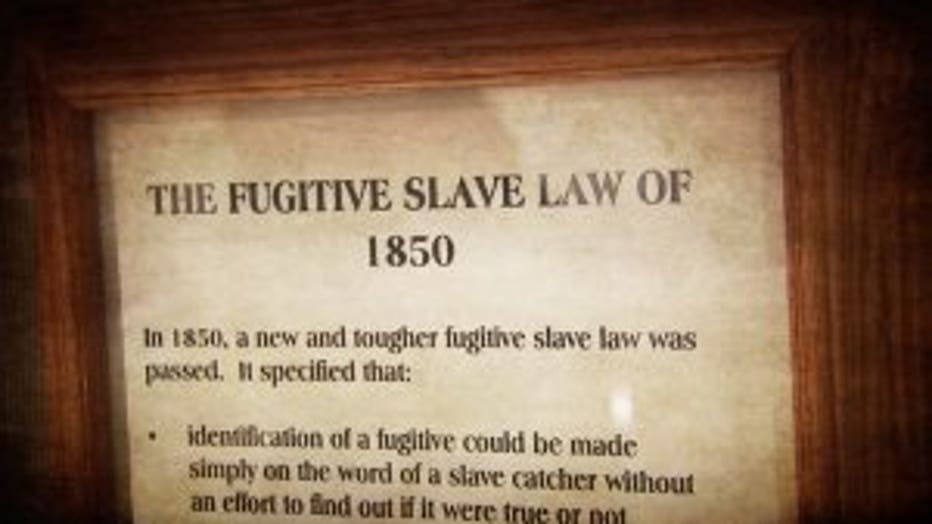

Dearborn's family, the Goodrich's and the other abolitionists risked hefty fines and jail time if they got caught, not to mention the risks taken by the runaway slaves. And so many times there was no conversation whatsoever," Dearborn said about the transport. "The slaves were brought in they were not looking. Potatoes were put in and they went off and they stopped and it was at night and they were unloaded. They didn't watch. And, they were taken away."

Dearborn said her family knew it was worth it. Her great-grandmother never mentioned being afraid."No, they did what they had to do. that was how they felt about it. It was against God's principles to be for slavery."

She's proud to call them family. Proud to have grown up in Milton. "And, I think I was very fortunate to have these ancestors and to have them live long enough so that I knew some of them."

The Milton House Museum knew Vernum Hull as a Seventh Day Baptist at Milton, but it was connecting to Dearborn in 2016 that brought his role as an underground railroad conductor to light -- adding to the historical site's narrative.

CLICK HERE to learn more about the Milton House Museum.