Heroin addiction considered "an epidemic," and anyone can be impacted, even student-athletes

MILWAUKEE (WITI) -- Heroin addiction has become an epidemic across the country, including here in Wisconsin. It has invaded our schools -- not only in the city, but in the suburbs. A man whose addiction began when he was in high school in southeastern Wisconsin is trying desperately to break free from heroin's grip, and he's not the only one.

"It's definitely not a myth. It's actually very popular. Athletes are doing pills and other drugs," the man said.

He's a former Milwaukee-area high school football player who became addicted to heroin. He agreed to go on camera as long as his identity was protected. FOX6 News is calling him "Steve."

"I first got involved in it for pain. I was prescribed vicodin. From there, my use escalated because I like the way I felt," Steve said.

Steve's drug use changed from taking drugs when prescribed to him, to finding them when and wherever he could.

"On the football field, it made me feel like I could hit harder, I could run faster. I was more relaxed. But in reality, I wasn't performing as well as I could have been," Steve said.

The consequences off the field were far greater.

"It takes control of almost every aspect of your life when all you want to do is get that pill inside of you -- or whatever your drug is. When it escalates to you, to me going through friends' medicine cabinets, trying to get my hands on anything that I could," Steve said.

Because Steve didn't have a job, he supported his addiction by selling pills to other students in school.

"Every single time I did it, I said 'I know it's wrong. I don't want to do this,' and then something flips in my brain and says 'it doesn't matter,' you know? 'I don't care,'" Steve said.

After high school, Steve played football in college for awhile -- but soon he became hooked on prescription pills he says were easy to get. He entered inpatient care and an aftercare sober house six month program, but he only stayed for two months. He was kicked out of his family's home, and soon, the homes of several friends.

"I thought that I could control it, and as far as I know, I think that a lot of people think that they can control it. But in reality, I couldn't, you know? It had taken over my life. It was more embarrassing because I couldn't control myself, and the disappointment in myself was mostly because I had to look in the faces of the people that I loved and seeing the expression of true disappointment is heartbreaking," Steve said.

Today, Steve is living day-to-day and moment-by-moment, trying to avoid a relapse.

"It is always in the back of my mind that 'hey, I know this person,' 'hey, I can go get drugs or something like that.' My main focus right now is that I don't have much else in my life. I can't lose anything else," Steve said.

Steve says he feels school officials, coaches and especially parents can do more in the war against heroin by having students tested.

"Don't get involved in drug-related activities because it can take over your life. It can happen anywhere and it does happen everywhere. If I was to get an ultimatum back then -- 'either I stop getting these reports from your family that you're doing drugs or you're not going to start on Friday' that might have helped. Sure," Steve said.

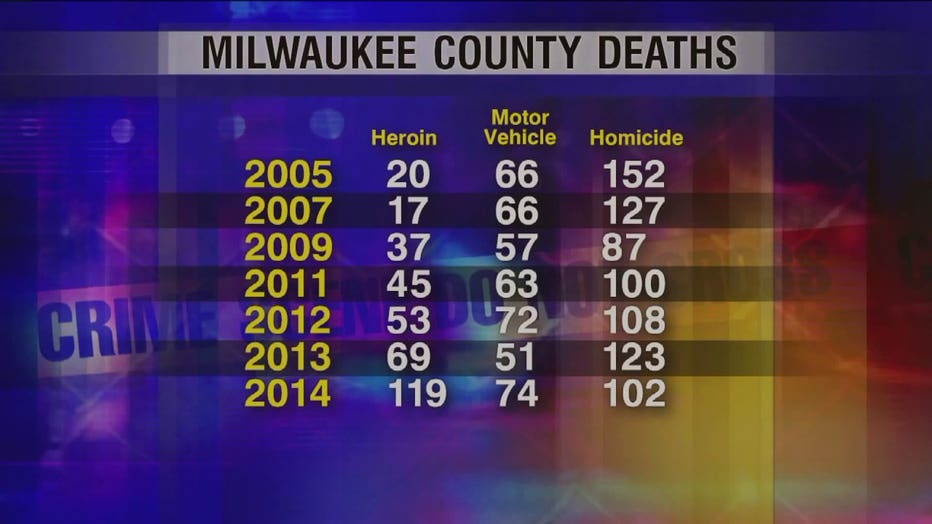

Sara Schreiber is the toxicology director at the Milwaukee County Medical Examiner's Office. Stunning statistics released last month show heroin-related deaths have outpaced traffic deaths and homicide for the first time -- jumping 72 percent.

"It kind of started out that it was perceived as being just an inner-city problem, but that it wouldn't inject itself into the suburbs and the more affluent areas of the state or the county, and that certainly has proven to be a false thought. The cases are broad-reaching. The stats that we have on death caused by heroin, the ranges are from 19 to 71 and anywhere in between. The average age is about 41, so this is not just a drug used by teenagers or 20-somethings," Schreiber said.

Years ago, the word "heroin" elicited fear. Not today. It doesn't cost much, and dealers can spin the truth to make anybody feel that the intoxicating high far outweighs any consequences -- which is dead wrong.

"That's quite scary, because at least you had the fear factor in place years ago -- just because of the fear of the word, but if the word's not scary anymore to the user, it certainly still is to their families and their loved ones that they leave behind," Schreiber said.

Schreiber sees firsthand the dangers of going near heroin because it is extremely addictive and deadly. The numbers don't lie.

"The first time that they use heroin it gives them their biggest high. It gives them the most euphoria, and they love that. So subsequently, they're trying to achieve the same response and their body doesn't give them the same response. So you do it again and you take more and you do it more frequently and you just crave it and crave it and crave it until you just can't get enough of it anymore. And you end up taking too much, and it ends your life," Schreiber said.

So what can be done?

"Not wanting to believe that it could happen to a good suburban school fosters the environment for addictive behavior," Jacob Jansen said.

Jacob Jansen was once a star high school swimmer in the area who almost drowned in a pool of drug abuse. At his lowest point, he faced 57 years in prison. Jansen is one of the lucky ones, and now, he is a counselor whose mission it is to help save the lives of others.

"Addictive behaviors live in the shadows. Recovery demands exposure. I've been to a lot of funerals. I've seen a lot of people die in my arms to this addiction. These are not bad people trying to get good. They are sick people trying to get well," Jansen said.

---

Linda Lenz knows the pain of losing a son to heroin. Today, she spends nearly every waking hour trying to prevent what happened to her from happening to any other family.

Canton Lenz

Lenz and her husband Rick lost their son Canton at age 30 to a genetic disorder. On the day the family traveled from their home in Muskego to California to scatter Canton's ashes, Canton's younger brother Tony confessed that he was hooked on heroin.

"When his brother passed away, we found out in a second -- like you can drop a piano on my head -- that he was addicted to heroin. I thought he was crying because his brother died and he said 'no, I'm an addict.' He always lifted weights. He was a runner, and I think looking back, 20/20 hindsight, when he stopped running I noticed there was a change in his behavior. The changes looking back were so obvious, but when you have a child who never caused you any problems, you don't see them," Lenz said.

Tony had it all -- good looks and a 4.0 grade point average -- but the heroin addiction was sucking the air out of his lungs, and his journal reflected that. Tony wrote: "All of the love that I feel from my family comes with so much shame and guilt. My picture perfect life being flushed down the drain while everyone watches -- throwing in life vests, trying to help. I can be helped. Unlike Canton, my brother, I have a choice. Instead of being a selfish person, I need to turn my life into something meaningful."

Tony Lenz

With treatment, Tony was healthy and happy for a period of time, but he relapsed. On February 12th, 2013, Tony went out with his girlfriend and others, and he never came home.

"He was found dead in a parking lot in Milwaukee the next morning at 10 o'clock. It was a heroin overdose. A lot of times, the kids that pass away, if they don't use for an extended period of time, they'll go and they'll shoot what they always would use, and they overdose. Their bodies aren't used to it anymore," Lenz said.

Tony Lenz was 23 years old. Within a span of less than three years, Linda and Rick Lenz had lost two sons.

"I don't believe we've fully accepted it. I really don't know how to think he's not coming back," Lenz said.

In the midst of her grief, Lenz decided to do something.

"I hate heroin. It's an entity that exists, and that's how I fight it right now," Lenz said.

Lenz has launched the non-profit: StopHeroinNow.org.

"The first week it was out, there were 68,000 people that passed through that page. My heart dropped because I never would have believed that it was that huge. There's not a person that I talk to that doesn't know someone that's an addict, who's in recovery or something," Lenz said.

Lenz believes battling heroin must start with education in schools, because prevention is the best medicine. Recovery rates, she says, are bad.

Whether speaking to groups or urging high school administrators, teachers, coaches and even state legislators to get involved, Lenz's mission, inspired by the memory of her son, is to try to help save lives.

"It's everything to me. I feel like he's watching over me and needs me to do this. Sometimes I think when I do these things and I speak out, maybe I'll get him back -- which is crazy, because that's not going to happen, but maybe I can help some other parent," Lenz said.