Kids in crisis: Suicide among young people in Southeast Wisconsin on the rise

Kids in crisis: Suicide among young people in Southeast Wisconsin on the rise

Kids in crisis: Suicide among young people in Southeast Wisconsin on the rise

RACINE — More kids in Wisconsin are killing themselves. Suicide, especially among young people, is a public health crisis that affects all of us.

Abigail Goldberg, age 13

After an extensive review of medical examiner reports in Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, and Waukesha counties, we've calculated that in the last five years in Southeast Wisconsin 71 kids and teenagers have died by suicide. Some were as young as 11 years-old. Seven young people have already taken their lives in 2015.

Cameron Langrell, a 15-year-old freshman at Horlick High School, died by suicide earlier this year. His parents, Jamie and Eric Olender, have chosen to speak openly out about his death in an attempt to help other kids who are struggling.

Tyler Webb, age 16

Cameron was a transgender teenager. We are referring to him as Cameron because, his parents say, he had not asked them to refer to him by any other name, or with female pronouns.

"Cameron was just beginning his journey," says his mom, Jamie Olender. "A transition journey, whether he wanted to see that through or not, had just begun."

Cameron's parents say they supported him, and urged him to be himself, no matter what.

Cameron Langrell, age 15

"He was just trying to identify with who he wanted to be," Jamie says. "He never asked to be called anything other than Cameron, never asked for pronoun changes or asked for anything specific, just wanted to be loved — and he was. He was loved by a lot of people.”

"In one of his notebooks he said he wore a mask every day and he pretended to be happy," Jamie said.

In Southeast Wisconsin, in the last five years, 71 people age 19 and younger have killed themselves (33 in Milwaukee County, 19 in Waukesha County, 12 in Racine County, and 7 in Kenosha County). Nearly half had barely celebrated their 16th birthdays.

Rachael Salmon, age 14

"People are shocked by the ages that kids are completing or attempting — younger and younger," says Martina Gollin-Graves, the President of Mental Health America of Wisconsin. Her organization is a leading voice for suicide prevention statewide.

"We all have to do a better job at understanding and recognizing the warning signs and acting upon what we think we're seeing — even if we're wrong," Gollin-Graves said.

Gollin-Graves says the truth is — teenagers aren't resilient.

"As adults we think, 'Oh gosh, don't they know it will be ok?' Nope. They don't know that," Graves said.

Katelyn Fennig, age 19

The statistics in Wisconsin bear that out. Michael Payne is the Medical Examiner for Racine County. Already this year in Racine, three kids have killed themselves.

"We have seen a steady increase of people under the age of 18 committing suicide," Payne said.

For every kid who dies, 11 others attempt.

"These kids they just started living and they haven't experienced life yet," Payne said. Payne also points out another trend: kids are killing themselves violently. Most die by hanging. Guns are the second most frequently used method in Wisconsin.

We spent months combing through medical examiner reports, trying to see trends and patterns in youth suicides in Wisconsin.

Here's what stands out:

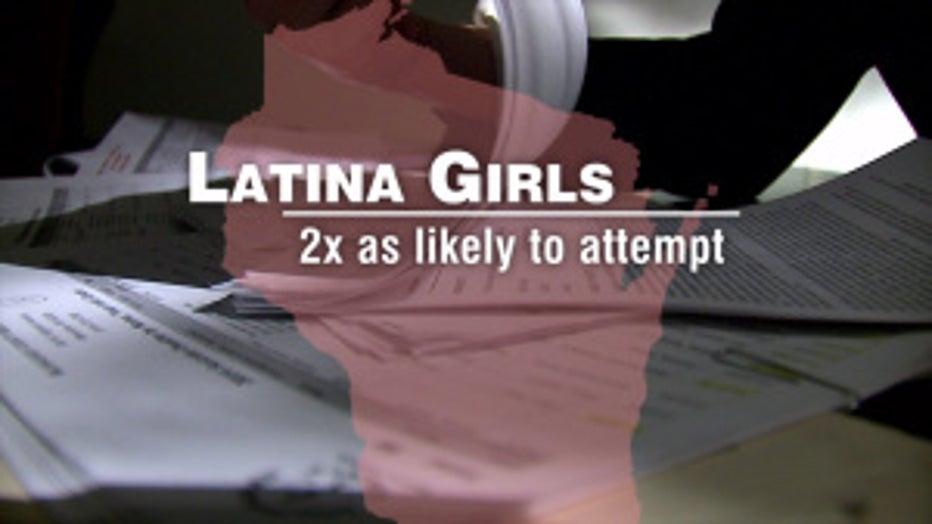

In Wisconsin, Latina girls are twice as likely to attempt suicide. Even though more white children die by suicide, minority kids in Wisconsin are more likely to try.

"We as a community and a state might want to take a look at what that means," says Gollin-Graves.

In the last five years, 13% of girls who killed themselves in Southeast Wisconsin had been recently sexually assaulted; 35% had problems with a girlfriend or boyfriend; 20% reported problems at school or with bullying; and at least 10% were gay, lesbian or transgender.

"If there's not support for our youth, whether they have sexual identity issues or not, they are going to break," says Gollin-Graves.

In fact, in a 2013 survey of Wisconsin high school students, 1 in 7 teens said they had seriously considered suicide.

"We know he had a very hard time fitting in at school," said Cameron's mom, Jamie Olender.

The Racine Unified School District (RUSD) has been hit the hardest, losing eight kids in five years. Cameron Langrell and Lexi Lopez were both transgender and they both attended Horlick High School. Lopez died by suicide in 2013.

Langrell's parents say Cameron frequently mentioned being pointed out in the front of the class, or singled out. They say he was sensitive, and really took it to heart when he felt like he didn't fit in.

RUSD says it has no record of Cameron or Lexi being bullied, but its schools are committed to working with parents and community organizations to wrap their arms around the kids who need it most.

"We need to work together to find ways to support students and make sure this doesn't happen again," said Stacy Tapp, a spokesperson for RUSD.

Tapp says the District is aware it serves students who sometimes need more help and more intense support. But she says mental health resources in Racine are scarce, and schools can't do it alone.

"The schools can do a lot and we work to do as much as we can, but it has to be a partnership," Tapp says. "It’s got to be the family and the community supports, too."

Tapp encourages families to reach out to schools when they suspect bullying or suicidal thoughts. She says kids can't get the support they need if the school doesn't know about underlying issues at home or elsewhere.

Even if Cameron and Lexi were bullied, though, there's not just one cause of suicide. Of the 71 kids who killed themselves in the last five years, more than a third suffered from depression or another mental illness.

Gollin-Graves says even teenagers who aren't depressed often make decisions on a whim.

Olender says her son Cameron was very impulsive, and suffered from depression.

"We had talked to the doctor about that a lot because if he thought he was going to jump off the roof he was going to jump off the roof," she said. "But there is no medication for that, it's just something that you have to learn to deal with."

Now she is left to deal with the reality of life without her child.

She encourages parents to have open communication with their kids.

"The life they live in high school right now, and even middle school and elementary," Olender says, "is so much harder than when we went to school."

WARNING SIGNS OF SUICIDE: The more signs someone shows, the greater the risk.

WHAT TO DO: