In the President Donald Trump years, California is set to lead on climate change

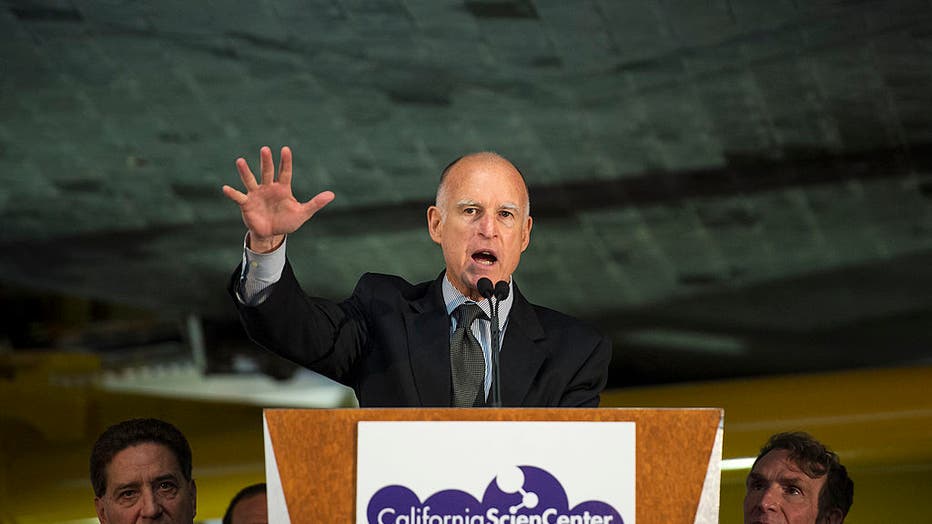

California Governor Jerry Brown speaks at the California Science Center (Photo by Bill Ingalls/NASA via Getty Images)

By Lucia Graves for the Tribune Media Wire

Even before the election of President Donald Trump—who has called climate change a "hoax," threatened to dismantle the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and sworn to withdraw from the Paris Agreement on carbon dioxide emissions—California, more so than U.S. federal government, was acting like the planet's de facto leader on climate change.

At the 2015’s Paris climate talks, the state showed up like any other major country, with representation from businesses, elected officials and state-based non-governmental organizations (NGOs). "Barely any other state sent anyone," California billionaire environmentalist Tom Steyer said. "We sent everyone."

That year, Steyer was co-chair of the state's business delegation, which he attended with Governor Jerry Brown (D). In the lead-up to talks, Brown behaved more like a head of state than many actual heads of state, meeting with everyone from Pope Francis to the president of China.

But in the wake of President Trump’s inauguration, Brown is reportedly preparing to act even more like a world leader than a state leader on climate change because, given President Trump's nominations of former Exxon CEO Rex Tillerson to lead the State Department and climate denialist Scott Pruitt to lead the EPA, there's plenty of cause for concern that the United States could back away from decades of progress on environmental protection.

"In every one of those cases, he's nominated someone who's deeply troubling,” Steyer said. “Not because of what's happening in the confirmation process, but because of what they've done in their lives and what they've said previously."

"I think it is very hard for federal officials whose money comes from oil and gas companies or oil and gas entrepreneurs to vote against oil and gas," he added. "I wish it were more complicated than that. I'd like to say it's more complicated than that. But that's the only thing I can see."

President Trump's transition team demanded early on that the EPA release the names of everyone in the agency working on international climate change treaty negotiations, for instance. And, in a leaked memo, reported by Axios Monday, stated that President Trump wants the department to completely stop funding scientific research.

So it's little wonder then that Brown feels a need to step into the void, particularly given that his state has a history of doing so: in the face of inaction by the Bush Administration, for instance, California passed greenhouse gas emissions standards, years before President Obama's EPA tried to do so. Recently Brown promised "California will launch its own damn satellite," if President Trump "turns off the satellites" run by the federal government that provide critical climate data.

California already leads the way—as explicitly allowed under the terms of the 1970 Clean Air Act—on national fuel efficiency standards for cars with a statewide program that Brown, then the state's attorney general, helped defendagainst interference by the Bush Administration nearly a decade ago.

And in the weeks leading up to President Trump's takeover, Obama's EPA worked furiously to shore up its 54.5 mile per gallon Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards before handing the reigns over to the President Trump administration—standards for which the state of California strongly pushed even after the federal government signed off on California's previous CAFE standards.

Steyer, the hedge fund manager-turned philanthropist, said "when we're talking about the miles per gallon rule that the federal government adopted … that's really a California rule that the federal government adopted subsequently."

But if President Trump cuts the CAFE standards, California will be back in the driver's seat. As the largest market for cars in the country—and world's sixth largest economy overall—California has serious market power when automakers decide how to design their vehicle, which is why the auto industry actually participated in the negotiations over the 54 MPG standards and initially supported the results. (Shortly after President Trump's election, the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers sent President Trump an eight-page letter asking that the standards be delayed and/or reformed.)

California state senate leader Kevin De León isn't holding out hope that President Trump won't implement the policies he's promised or telegraphed he would support. "California is not waiting for Congress to pull its head out of the sand," he told a conference for meteorologists in Lake Tahoe in early January. "We are a world leader on climate change, and we’ve been hard at work building the clean energy economy of tomorrow."

As evidence, De León cited the state's decade-old cap on greenhouse gas emissions and newer measures, like the one committing the state to get half its electricity from renewable sources by 2030, and another vowing to cut emissions to 40 percent below 1990—the strongest emissions reduction goals in the country.

"We’re setting an example for the nation to follow, if not at the federal level then state by state by state. And it’s working," he concluded.

California already has agreements to link carbon markets with several states and two Canadian provinces as a way of realizing greater emissions reductions— though they're being challenged in court— and has international cooperation lined up for its cap-and-trade policies. Another initiative, the Under 2 MOU initiative, unites governments from 160 jurisdictions in 33 countries in a pledge to move forward on climate change, no matter what happens nationally.

But California's actions on environmental policy without the blessing of the EPA isn't limited to the state level.

A national list of cities transitioning to 100 percent renewable energy maintained by Sierra Club reveals three of the four largest cities in California (San Diego, San Jose and San Francisco) have committed to achieving the 100 percent benchmark in near future. Los Angeles is on its way to 50 percent renewables by 2030—no easy feat for the informal car capital of the country.

On the same Tuesday that President Trump was elected, Los Angeles voters approved a $120 billion commitment to public transit. L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti then joined mayors around the country in renewing their commitment to the goals laid out the Paris climate accords.

"Every city, every community, every individual has the power to fight climate change,” said Mayor Garcetti in a statement at the time. “We do not need to wait for any one person or government to show us the way."

Since Election Day, Garcetti's had his Chief Sustainability Officer Matt Peterson analyze the city's greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets to help reduce energy use in existing buildings by 14 percent before 2025 and by 30 percent before 2030, a goal Peterson said that the city is already on track to achieve.

Garcetti was also one of 48 mayors from around the country to sign off on an open letter just before Thanksgiving urging President Trump to tackle the climate crisis head-on; recent events suggest that the new president was not exactly a receptive audience.

For all the bravado, California going its own way on climate could make some things more difficult for the state. A President Trump administration could, conceivably, shrink the flow of money to some of the state's famous research institutions that have helped spark the green innovations so essential to the new climate economy, for instance. Other experts have posited the administration could nullify existing protections on clean air and fuel efficiency by halting enforcement of the Clean Air Act on the federal level, and challenge the state's special status under the act to set environmental standards that are more stringent than the federal government's.

There is, after all, some precedent for such things: California's 2007 move to set stricter vehicle emissions standards for the state than were authorized under federal law became a political football when a federal court upheld California's efforts, only to have the Bush administration use every tool in their arsenal to fight the court order.

However, whether California is able to maintain its higher environmental standards, even the sixth-largest economy in the world can't make a dent in slowing, let alone reversing, climate change on its own. Carbon dioxide doesn't recognize national or state borders, and the more there is in the atmosphere, the warmer the world gets. The United States is the world's second-largest carbon dioxide emitter; no matter what California does to curb its own emissions, if the President Trump administration radically reverses direction on climate change, as it looks poised to do, it will be small comfort.

And as any business man, even Steyer, will acknowledge, everything's more difficult when it can't be scaled up. "California can continue to be a leader," he said, "but there are reasons why we won't be as effective if we go it alone."