Clipped wings: How Gov. Walker's jobs deal at Kestrel Aircraft went wrong, leaving taxpayers on the hook

SUPERIOR –- Mark Liebaert looked across the bleachers at the fairgrounds that Kestrel Aircraft Co. had pledged to turn into a manufacturing plant for its next-generation airplane.

No planes were in sight. Nor were any workers.

“This really was our chance,” said Liebaert, the county board chairman whose kids had shown cattle at the fairgrounds. “We were hopeful that it was the snowball that was starting to roll for us in the right direction."

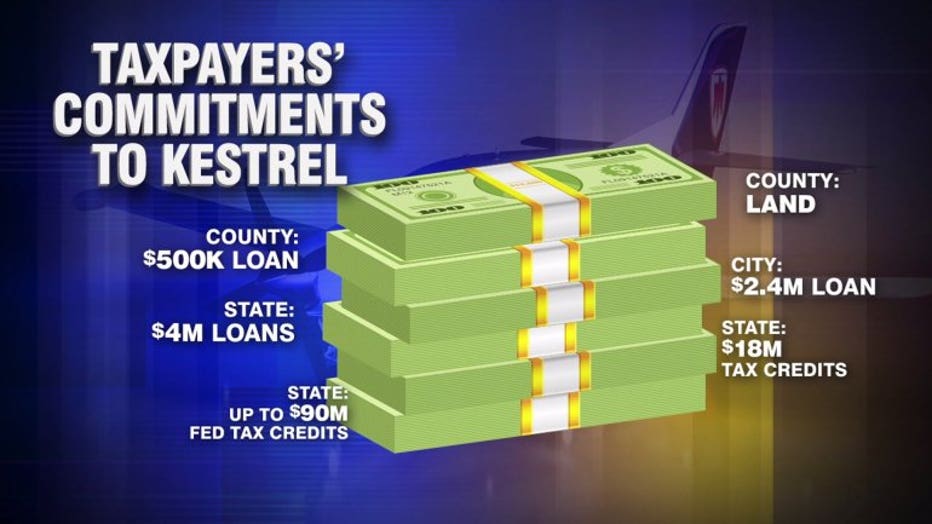

In the nearly six years since Kestrel executives and Gov. Scott Walker announced a partnership that committed $25 million in taxpayer money, Kestrel has defaulted on state loans worth several million dollars and has delivered a small fraction of the 665 promised jobs.

Now, as the state prepares to sign a contract with Foxconn Technology Group authorizing up to $3 billion in cash payments from taxpayers to the Taiwanese electronics company, state officials are threatening legal action to recoup losses from the Kestrel deal.

In turn, Kestrel’s top executive accuses the state of backing out on its initial promises, sending the deal into a tailspin. He predicts that he can still get the turboprop airplane to market, and says he may build it outside Wisconsin because of a deteriorated relationship here.

Legal action

Kestrel has not made a payment on its two state loans totaling $4 million since November 2016 and owes $648,000, according to officials at the Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation.

"We’ll continue to pursue whatever rights we have to protect the investment that was made," WEDC Chief Executive Mark Hogan said in a brief comment when asked by FOX6 News this month about the Kestrel deal.

Hogan, through agency spokesman Mark Maley, declined an interview to lay out his agency's plans. WEDC has not taken Kestrel to court, and it's unclear how much money it could recover that way.

The Kestrel revelations are the latest in a spotty record for WEDC, the job-creation agency that Walker and legislative Republicans created when they took control of state government in 2011. WEDC is being closely monitored for how it protects taxpayers in the final contract with Foxconn.

A WEDC board member said last week that the agency had allowed a "nuclear bomb" into the contract that would've let Foxconn keep taxpayers' $3 billion even if the company left the state or violated the terms of the deal. Hogan scuttled a possible October 17th vote after staff found the problem.

Kestrel's workforce shrinks

Kestrel, through parent company One Aviation, laid off some of its 25 workers in Superior in October amid continued uncertainty about its future in Wisconsin.

Alan Klapmeier, the company's CEO, declined to say how many employees were affected but said they represented "cuts" not a "closing" of the small Superior operation.

At no time in the past five years has Kestrel reported having more than 57 workers in Wisconsin – less than 10 percent of its promised workforce. The state has paid $717,500 in job-creation tax credits to Kestrel and has made no moves to recoup that investment. (The state promised $18 million in tax credits, but the total was contingent on the company creating all 665 jobs.)

By 2017, the company’s Wisconsin-based payroll shrunk to 25 employees, according to Kestrel’s annual report filed with the WEDC.

Largest project since World War II

When Walker flew into Richard I. Bong Memorial Airport in Superior in January 2012, he was about to announce the largest jobs deal his year-old administration had brokered. Kestrel had chosen Wisconsin over Maine, where a previous tax incentives deal had fallen through.

“This may be the largest economic development project coming to our community since the end of World War II,” then-Superior Mayor Bruce Hagen told a crowd gathered inside one of the airport’s hangars.

Klapmeier had local ties. He, along with his brother Dale, had turned Cirrus Aircraft into a success in nearby Duluth, Minnesota, before Alan Klapmeier was ousted from the company and launched Kestrel.

For Walker, there were political implications to the deal. The governor had won office less than 15 months earlier on the promise that he would create 250,000 jobs in his first term.

In January 2012, he was far from fulfilling that promise, and would have to face voters again earlier than anyone would've imagined: the historic 2012 recall election would take place that spring.

'A dream'

Klapmeier’s plan: build an airplane called the K-350 from composite parts that would be capable of flying farther on less fuel. Local officials saw the Kestrel deal as a necessary roll of the dice for a county with 8 percent unemployment and a reliance on heavy industry.

"The project was as big for Douglas County as Foxconn is for southeast Wisconsin," Liebaert said. “This was kind of a dream industry to come in here, not a smokestack-type industry."

Superior borrowed $2.4 million to give to Kestrel, and Douglas County provided a $500,000 loan plus land at the fairgrounds and an industrial park on Superior's west side. WEDC came through with the two loans and the $18 million in tax credits.

The Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority made the biggest bet, providing Kestrel $30 million in federal tax credits and pledging to help find two more $30 million allotments. (The cash amount that Kestrel received is around $9 million, not $30 million, because of a complicated formula used to allocate the credits, multiple people said.)

Finger pointing

Kestrel’s chief executive, Alan Klapmeier, blamed WHEDA officials for failing to deliver the first $30 million allotment of federal credits on time, and for not coming through with the two additional installments at all.

The entire deal collapsed about six weeks after Walker announced it because the delay in getting the first allotment caused a ripple effect with other investors, Klapmeier said.

“This is a story of integrity,” Klapmeier said during a late September interview at Kestrel’s office in a downtown Superior building that once housed the U.S. Postal Service. “The state did not do what it said it would do from the beginning, and then blamed us. And so, for that, I suppose I would broadly put the blame on the governor, on WEDC, and on WHEDA.”

The contracts between the state and Kestrel do make references to the second and third allotments, which would have – when added to the initial $30 million – totaled $90 million in federal tax credits by 2013.

“The Borrower shall have received the rights over time to an allocation of $90 million in New Market Tax Credits through the Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority,” reads one of the loan contracts between Kestrel and WEDC.

Klapmeier said everyone involved agreed that the full allotment was necessary to make the project successful. But Kevin Fischer, a WHEDA spokesman, said WHEDA never made promises to deliver the second and third allotments, only to help the company pursue it.

Red flags

There were early signs that the deal wouldn’t work out.

In 2012, WHEDA officials noted that “there is no way to know that the K-350 will receive certification” from the Federal Aviation Administration “and, therefore, no real way to guarantee that the larger goal of an aircraft plant will be realized,” according to documents obtained through an open records request.

Kestrel had not provided documentation providing it would be able to raise enough money for the project during the key startup years of 2013 and 2014, according to the documents. The company was already delinquent on its reporting requirements to Maine, according to meeting minutes from a June 5, 2012 WHEDA committee meeting.

At that meeting, WHEDA board chairman Lee Swanson called it a “very risky, speculative investment more akin to venture capital.”

WHEDA secretary Wyman Winston – a Walker appointee – responded by talking up the potential jobs in Superior, and members ultimately approved the New Market Tax Credit deal.

Problems started early

Kestrel's business model sputtered despite the approximately $16.6 million in assistance from local and state loans, state tax credits, and federal tax credits.

Klapmeier said he used the funding to hire engineers for the project. The company began missing payments on the two $2 million WEDC loans in late 2013, agency officials said.

In June 2014, WEDC officials and Klapmeier agreed to restructure both loans. Under the deal, all payments were deferred until November 2014, after which Kestrel would make interest-only payments for one year. The deal also pushed the final due date to 2020 from 2017.

But Kestrel made only periodic payments, missing five of its 12 scheduled payments in 2016 and all of them in 2017.

Former state Sen. Bob Jauch, who worked with both sides in an attempt to find a resolution, said the state acted in good faith. He said the deal went sideways because of what he called Klapmeier’s “selfishness,” and said state officials need to get tougher on the businessman.

“At some point, they have to say, ‘Enough is enough,” said Jauch, D-Poplar, who retired in 2014. “They need to have some provisions that say, ‘We will not bankroll you.’ This is not a gift. These are loans.”

Trip to China

Despite the missed loan payments in late 2013, WEDC wasn’t done offering Wisconsin taxpayers' money to the struggling company.

On April 7, 2014, WEDC promised to reimburse Kestrel up to $10,000 so that Klapmeier could attend an air trade show in China.

Klapmeier told FOX6 News he never asked for the money, which he characterized as an offer from WEDC made during the loan restructuring process that happened that year.

Kestrel withdrew from the grant process, and WEDC never provided the $10,000.

On the range

In 2015, Kestrel merged with an aircraft maker called Eclipse to form the company One Aviation, of which Klapmeier is chief executive.

The company is based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Klapmeier said his business plan is to redesign the Eclipse 550, a jet that’s currently in production, and funnel revenue from sales of the Eclipse into the Kestrel turboprop project.

Klapmeier has a mock-up of the K-350 that lacks wings. But it isn't in Superior, or even Wisconsin.

It sits in an airplane hangar in Grand Rapids, Minnesota.

One Aviation has a facility at the Grand Rapids-Itasca County Airport to build parts for the Eclipse redesign. In late 2016, the Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation Board gave One Aviation a $1.5 million loan to move some operations to the airport, where One Aviation now has three employees.

But Klapmeier -- who previously sought state assistance in Maine and Wisconsin -- hasn’t touched the Minnesota loan, said Mark Phillips, the IRRRB’s commissioner.

When asked if he would build the Kestrel in Minnesota instead of Wisconsin, Klapmeier told FOX6 News, “The thought certainly crosses my mind.”

Disappointment in Superior

An hour and a half to the southeast of Grand Rapids in Superior, the only proof to the outside world of Kestrel's presence is a small “One Aviation” sign on a marquee that lists all of the tenants at the former Post Office building.

Local officials concede it is highly unlikely that the Kestrel airplane will be built in Superior.

Superior Mayor Jim Paine said he, too, was considering legal action against Kestrel. The city must pay more than $300,000 a year on Kestrel's loan, which represents 1.1 percent of the overall $28 million budget, Paine said.

“There is a reasonable limit, and we are approaching it,” Paine said when asked when he would pursue legal action against Kestrel. “I think it’s fair to say, when you borrow money, you should pay it back. None of the banks in town have any problem saying that to any of the homeowners.”

Douglas County officials are watching, Liebaert said.

“If either one – the state or the city – pulls the plug on this, I think it’s a done deal. It’s over,” he said. “And we’ll have to pile on, obviously.”

The Wisconsin Indianhead Technical College closed a composites program that trained people to make parts for the Kestrel plane. Instructor Dave Crockett said he thought the classes could've continued without Kestrel, but said administrators had decided otherwise.

"It was a loss to the state," Crockett said in an interview outside the WITC campus in Superior. "It was a loss to the school, for what could've been here."

'Difficult' financial situation

Kestrel’s balance sheet provided by WEDC shows the company lost $4.3 million in 2016. The company was evicted from a facility in Brunswick, Maine in October.

Klapmeier said the state and local governments would get little if they pursued the company in court because Kestrel is responsible to its lenders.

He described his own financial situation as “difficult" and said he bet his future on the company.

“Our job is to try to save the company. Try and figure out how we can employ the people here, build the airplane, generate the cash that still makes this work,” he said. “If it doesn’t, will the taxpayers get all their money back? Certainly not.”

Jim Caesar, the head of the Douglas County Revolving Loan Fund who was described by numerous people as the intermediary between Superior, Douglas County and Klapmeier, did not return phone calls seeking comment.

Comparison to Foxconn

WEDC's early years are marred with deals like the Kestrel one; the agency made some awards without proper reviews, a 2015 audit found.

Multiple companies have failed after getting taxpayer-backed loans. In one case, Green Bay businessman Ron Van Den Heuvel faces federal charges for allegedly defrauding WEDC of $1.1 million while running food wrapper maker Green Box NA and using the money to buy a luxury SUV, football tickets, and make court-ordered payments to his ex-wife.

WEDC's public threat of legal action against Kestrel coincides with intense scrutiny over the agency's handling of the Foxconn deal.

State lawmakers have approved up to $3 billion in cash payments to Foxconn if the company follows through on promises to build a massive plant for its Sharp television brand in southeastern Wisconsin and hire 13,000 workers.

Democratic state Sen. Tim Carpenter, a WEDC board member, is demanding to see the contract before a vote that could happen November 8th. Usually, the WEDC board sees a staff review of the contract, but not the contract itself.

The undoing of the Kestrel deal leaves local officials unsure if they'd do it again.

“If there’s a lesson to be learned, that’s what it is: “It had better be a project so valuable, a prize so grand, that we’re willing to risk a substantial hit (if it doesn’t work),” Paine said. “This is a story of a project that didn’t work out.”

Sitting in the grandstands at the Douglas County Fairgrounds rodeo arena, Liebaert called it a once in a lifetime opportunity.

"If it doesn’t work out, if the county loses the money, I would have to say that we were sold a bill of goods, that it wasn’t a possibility for this to be done," he said.