'Life-changing:' Nonprofit Feast of Crispian brings together actors, veterans to help them overcome trauma

MILWAUKEE -- For members of the United States military, the hardest battles fought often come when they return home. Through the Milwaukee VA Medical Center, one group of vets has found an unlikely form of therapy -- putting their issues on stage.

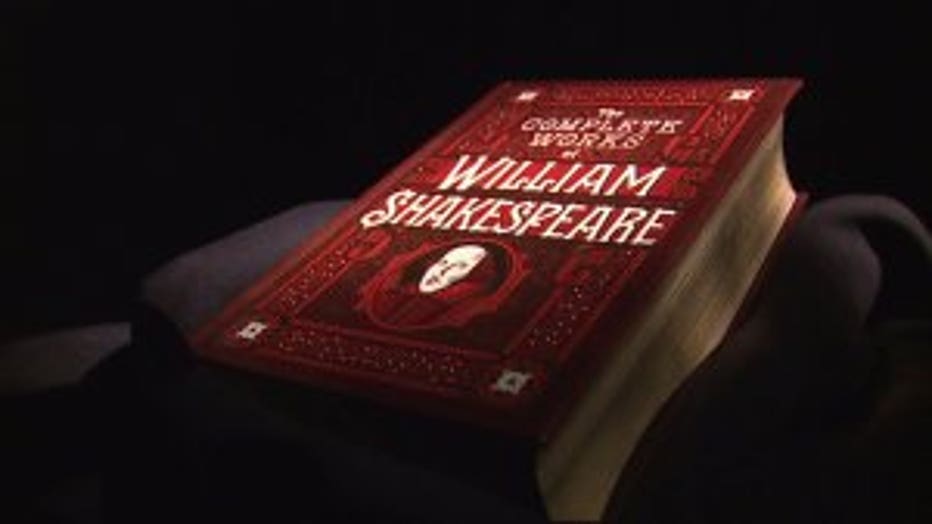

William Shakespeare wrote, “A man can die but once.” Raymond Hubbard would beg to differ.

The way Hubbard sees it, he's died twice already.

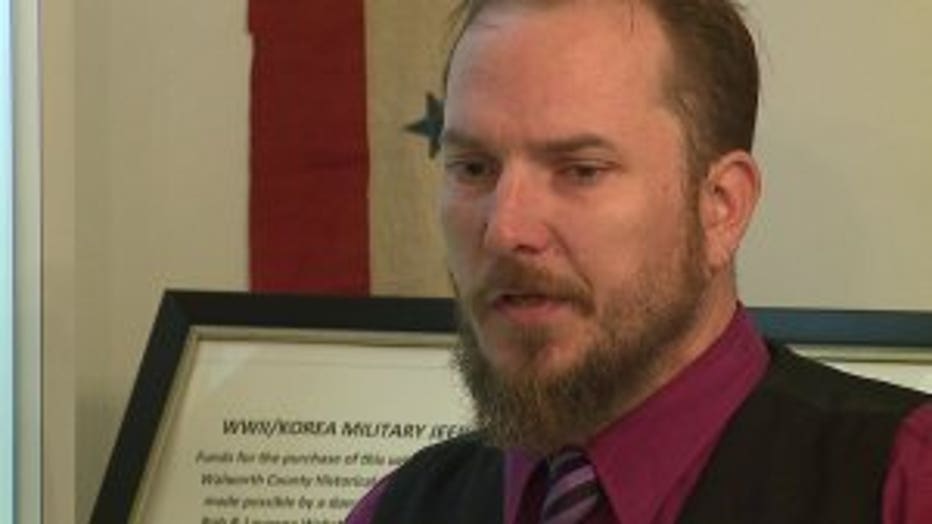

"I was one of two casualties during our unit's tour," said Hubbard.

Raymond Hubbard

Flashback to July 4, of all days, in 2006. Specialist Hubbard of the Wisconsin National Guard was in Iraq, just a few weeks from coming home, when he left his guard shack.

"I’d went out there that day because we’d flipped a coin," said Hubbard.

That flip meant he was out in the open when an enemy rocket blew up 20 feet in front of him.

"The doctor had his hand in my neck, telling me to keep on talking to him, because I no longer had a pulse," said Hubbard.

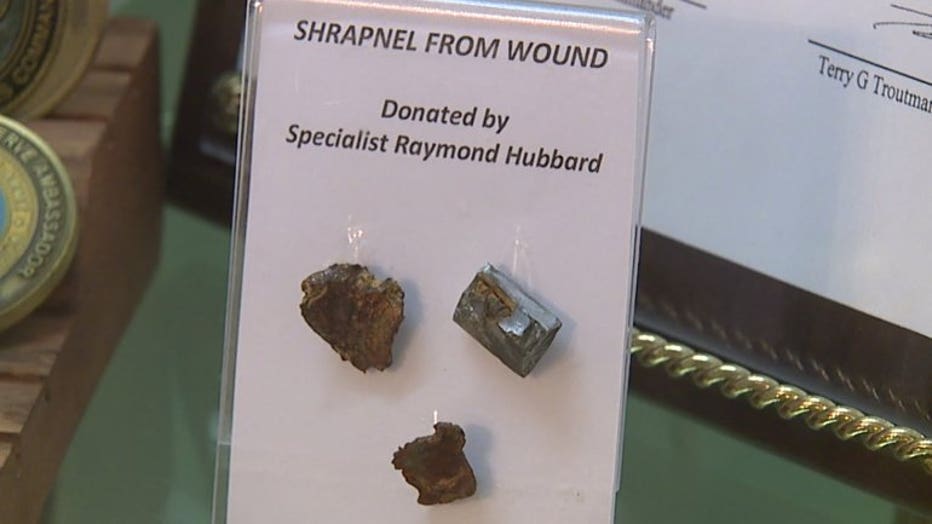

Shrapnel tore apart his body, took away his leg and left Hubbard in a coma.

Raymond Hubbard

"I had thought that I had died. I had thought that I had floated over the funeral home in Delavan, Wisconsin, and I had thought that I had seen a line-up of mourners going around the block," said Hubbard.

Instead, life would not be that simple. Back home in Walworth County, he spiraled downward -- from morphine and OxyContin to heroin and an overdose.

"The next day, I woke up with tubes down my throat and handcuffed to my bed," said Hubbard.

The decorated soldier was stripped bare.

Raymond Hubbard and Carissa DiPietro

"For the pain to be as such that I didn’t care anymore about my legacy -- that was a revelation," said Hubbard.

Some of life’s scars are impossible to ignore. Other wounds -- just as deep -- lie below the surface.

"This tattoo says, 'Healing,' because I’ll always be healing, but I’ll never be healed," said Carissa DiPietro, Army veteran.

DiPietro’s battles began the moment she joined the Army.

"My purpose now is to tell my rape story. I was raped by my recruiter," said DiPietro.

That man promised to make her life at Fort Bragg a living hell, but a few years later, a meeting with her lieutenant colonel was far worse.

"He said that my daughter, Ashley, was killed. They didn’t have all the details yet," said DiPietro.

DiPietro's ex-husband had beaten their 5-year-old girl to death.

"He beat Ashley. Over 100 blows. She didn’t whimper once -- and then he picked her up and he threw her in the bedroom and she hit her side on the bedpost, and that’s when she started passing away," said DiPietro.

She cried at the funeral. She cried after the trial -- and then the tears stopped for years after that.

"I’d go to the cemetery. I’m like, 'OK. Cry. Cry. Cry. You’re supposed to feel bad,' and then I’d hate myself for not crying," said DiPietro.

Crippled by grief she could not express, DiPietro barely left her room.

"If my kids wanted to spend time with me, they’d eat dinner in bed with me," said DiPietro.

Then, she saw a flyer at the Milwaukee VA Medical Center for something called "Feast of Crispian."

"It was literally life-changing. I realized I was missing the camaraderie of the military," said DiPietro.

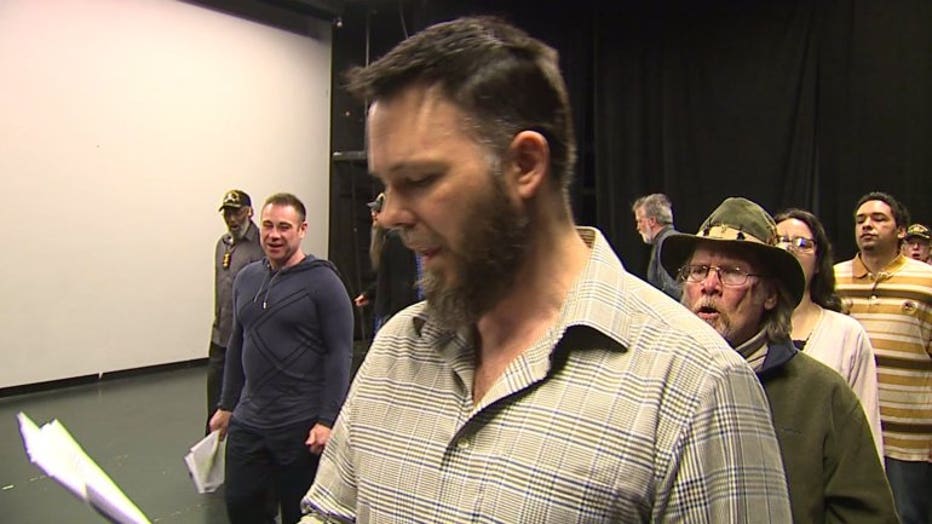

Far from the deserts of Iraq, the mountains of Afghanistan or the jungles of Vietnam, America's wars over the last 50 years are played out on a basement stage at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

"Mama, Mama, can’t you see what the Corps has done to me? Put a rifle in my hands. Taught me how to kill a man. If I die in a combat zone, box me up and ship me home. Pin my medals upon my chest. Tell my dad I done my best. Give my daughter $200 grand. Tell her her father was a hell of a man. Company halt. Left face. Mama, Mama, can't you see what the Corps has done to me? Put a rifle in my hands. Taught me how to kill a man."

The weapons in these fights are the words of William Shakespeare.

"What’s amazing to me is that it’s still relevant today -- those words from 400 years ago," said DiPietro.

Feast of Crispian is a nonprofit organization that involves professional actors using the Shakespeare's language as therapy to unlock deep-seated trauma and pain.

"There’s a scene for whatever situation you’re going through," said DiPietro.

"Maybe say things about getting drunk and losing your stripe by using Cassio’s words to say them instead of your own," said Bill Watson, founder and director of Feast of Crispian and UWM associate professor.

"There was some question that they asked, I can’t remember what it was, and I said, 'I was raped by my recruiter.' And it was just something I hadn’t said since 1999," said DiPietro.

"'I haven’t told my husband. I haven’t told my therapist' -- and they tell us," said Watson.

"When they tell their stories, it’s as if that weight gets spread around by everybody that’s hearing it," said Nancy Smith-Watson, co-founder and program director.

"They gave me a prompting question and I stopped in my tracks and I just started crying, and I’m like, 'Where is this coming from?' It was just so amazing," said DiPietro.

May 23-26, a wider audience than ever before will be listening.

"They felt -- and this was from them -- that it was time to go ahead. They were ready to tell their stories," said Jim Tasse, co-founder and UWM senior lecturer.

With the backing of the Milwaukee Rep, they’re hosting the inaugural National Veterans Theater Festival -- a series of shows putting the spotlight on the vets’ own experiences -- in their own voices.

"It’s given me more of a sense of my calling and why I’ve died twice and come back," said Hubbard.

"These aren’t people pretending to have lived this. These are people who’ve lived it, and that’s a very different sort of thing. That’s skin in the game," said Tasse.

Feast of Crispian gets its name from a speech in which Shakespeare coined the phrase: "Band of brothers."

"In wartime, you’re fighting for the person to your right and your left. I'm on that stage for all those others on stage with me," said Hubbard.

"I have a friend that says, 'Every veteran needs a platoon, and every platoon needs a mission,' and I didn’t have any of that, and with Feast of Crispian, I found that," said DiPietro.

At the end of this mission, there's only acceptance and applause.

The National Veterans Theater Festival runs May 23-26. All performances are 90 minutes or less and include a talk back immediately following the performance.

Tickets are $30 for adults per play, $20 for veterans per play, and $25 for seniors and students per play -- or three plays for $75 and five plays for $100.

CLICK HERE to learn more.