"Doesn't feel right:" Elderly patients with dementia handcuffed after caregivers call 911

Elderly patients with dementia handcuffed after caregivers call 911

Elderly patients with dementia handcuffed after caregivers call 911

MILWAUKEE — There's an estimated 48,000 people living with Alzheimer's in southeastern Wisconsin. Half of those people don't know it yet, because they haven't been diagnosed. But nearly all of them will eventually need care.

"There can be a three-month wait-list to try to get help for your loved one. I don’t have three months," said Tom Kelley, who is living with dementia.

Even if you find care, there's no guarantee your loved one will be able to stay there for long, especially if they have challenging behaviors. Sometimes, when nursing homes or assisted living facilities can't handle a resident's behavior, they call police.

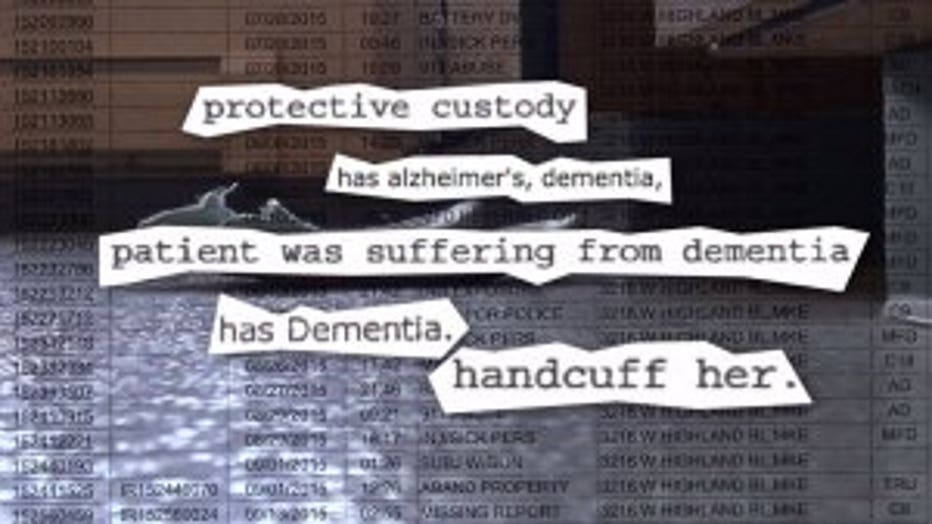

Research conducted by the FOX6 Investigators has found elderly patients with dementia are are often being handcuffed, after their caregivers call police. In some cases, they are even spending the night in jail -- waiting for the paperwork to get sorted.

"It's like a guaranteed way to make it worse," said Tom Hlavacek, the executive director of the Alzheimer's Association Southeastern Wisconsin Chapter.

The FOX6 Investigators reviewed hundreds of 911 calls from nursing homes in some of the largest jurisdictions in southeastern Wisconsin to see just how often police are called to deal with dementia patients.

We found dozens of reports where elderly people suffering from the disease were "causing problems" and nursing home staff "frustrated by their behavior"wanted them "relocated" to other facilities.

So they called the police.

Rob Gundermann, the public policy director for the Alzheimer's and Dementia Alliance of Wisconsin said this is not the way to handle situations with such vulnerable people.

"It just doesn't feel right. Handcuffs are for punishing people, or for people who have done something wrong and you can't trust them. They're not for dad who is having a medical issue," Gundermann said.

It happened to 73-year-old Shannon Wittal. Wittal was once an award-winning ballroom dancer.

Shannon Wittal dances the Paso Doble in 2014.

"She supported herself, us kids, had her own life and her own activities — paid her own bills, had a job, always did her own finances," said Brenda Mueller, Wittal's daughter.

A few years ago, Mueller noticed her mother's behavior started to change.

"She wasn't sleeping at night. She'd be up wandering around," recalled Mueller.

Wittal's family chalked it up to old age, but things got worse.

"She still could recognize people, still could figure out what season it was, when Christmas was coming, all of that. Now, three years later, it's a whole different story," Mueller said.

73-year-old Shannon Wittal, who suffers from dementia, was handcuffed by police in 2016 after she hit a caretaker.

The dancer who once memorized complicated dance routines can't even read a clock now.

Wittal, in her early 70s, was diagnosed with dementia.

"She can no longer read a calendar, read dates, doesn't know what day it is," Mueller said about her mother.

Wittal's family sent her to an assisted living facility in Waukesha County. Mueller said the facility advertised that it specialized in dementia care.

On March 25th, 2016, a situation involving Wittal and staff member escalated, leading an administrator at the facility to call 911.

"It was just like, 'Oh my gosh, how can this be happening?'" Mueller said.

Police were called on Wittal — who had a urinary tract infection at the time — because she got aggressive with staff, including hitting a caretaker.

The 73-year-old was handcuffed and put in the back of a squad.

It's called an Emergency Detention (Wisconsin Chapter 51.15) or Emergency Protective Placement (Wisconsin Chapter 55).

An Emergency Detention is intended for an individual suffering from a mental illness.

A Protective Placement is intended for an individual deemed incompetent under Wisconsin Chapter 54.10 and who needs to be a long-term care facility or nursing care facility or who need services in the community.

In both situations, a caregiver sometimes calls 911. The police then decide whether to take the person to a hospital or a mental health facility, but only if they believe an individual is considered a danger to themselves or to others. Emergency detentions are no longer supposed to be used when dealing with individuals who have dementia, but some counties are still detaining people with the disease.

Tom Hlavacek, Executive Director of the Alzheimer's Association Southeastern Wisconsin Chapter

It's a practice the Alzheimer's Association of Southeastern Wisconsin has been working to eliminate.

"Why people put older adults in handcuffs — I'll never know," said Tom Hlavacek. "There are other ways of intervening."

Mueller says caretakers at the home where her mother lived, if properly trained, should have been able to calm her mother down before she spiraled out of control.

"People aren't trained to handle dementia patients properly and when they're not handled properly, it causes aggression," Mueller said.

Bette Leque feels there should be more training for caregivers of Alzheimer's and dementia patients.

It's a situation Bette Leque and her family know all to well. Leque says caregivers were sometimes unable to calm down her 100-year-old father, Ken Leque.

"They utterly failed him," said Bette Leque. "All of a sudden, we had gotten these calls that he was being transported, that he had hit one of the hospital staff."

Police handcuffed Ken Leque and put him in the back of a squad car. Bette Leque said hearing about what happened to her father was devastating.

Ken Leque was handcuffed when he was 100-years-old, and had a walker.

"How can somebody do that?" Bette Leque wondered. "And, I did not know where he went."

Leque was transferred in and out of 14 facilities in three months.

Bette Leque shared photos with the FOX6 Investigators that show bruises up and down Ken Leque's arms.

Bruises on Ken Leque's arms after being restrained.

"This should not be happening. These are the people who built the road that we walk on and this is not how we should be treating them," Bette Leque said.

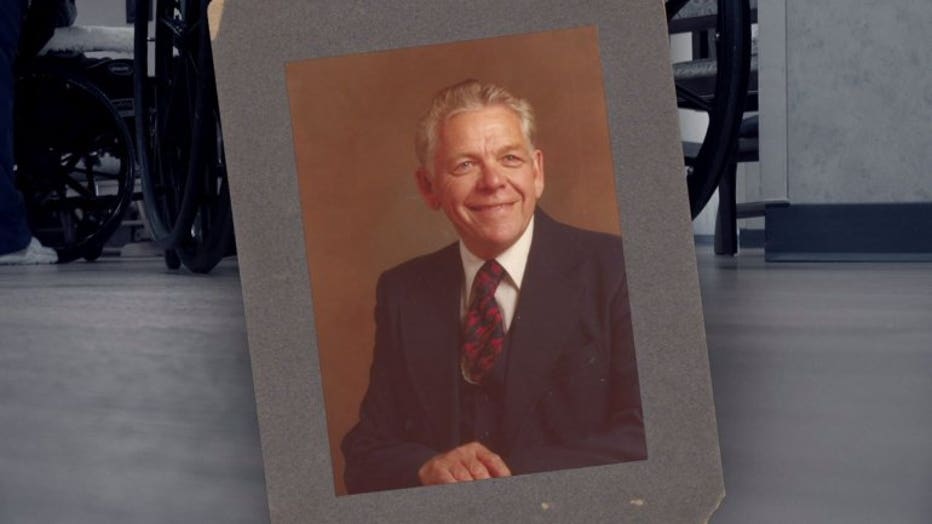

It's an issue that was highlighted years ago in Milwaukee County after a series of events involving Richard Petersen. In 2010, Petersen was 85 years old with late-stage dementia when he was handcuffed and bounced around to several different facilities.

At one point, the Petersens found their father tied to a wheelchair without a jacket or a pair of shoes.

"It was awful," recalled Jodi Petersen, one of Richard Petersen's daughters. "Dad was moved two or three times within a very short period of time from one room to another. He didn’t know where he was. It’s not good for anyone who has dementia and/or Alzheimer’s. They need familiarity."

Soon after, Richard Petersen developed pneumonia. He was taken to a hospital, where he died.

Richard Petersen died after being shuffled from facility to facility. His family found him tied to a wheelchair.

"Something really, really needs to change," Jodi Petersen said.

Petersen's family spoke about their experience, hoping it would never happen again.

"There are more people like my dad. My dad is not alone," Jodi Petersen said.

Petersen's death led to the creation of the Alzheimer's Challenging Behaviors Task Force. The group looked at developing ways to change the system to ensure a situation like Petersen's wouldn't happen again.

In December of 2010, the Task Force released a report called, "Handcuffed."

The report outlined the issue of handcuffing elderly people with dementia and Alzheimer's. It offered recommendations on how the issue could be changed.

In December of 2012, the Task Force released a follow-up report called, "We All Hold the Keys."

The report outlined the Task Force's work after "Handcuffed." It offered recommendations from four work groups established by the Task Force. The recommendations were aimed at making sure caregivers have the proper tools to care for patients, and that emergency personnel were properly trained.

Recently, the Department of Health Services released this report, detailing the need for mobile crisis units, to improve crisis responses for people with dementia. The authors of the report wrote: "The goal should always be to respond to a behavioral crisis in a manner that causes the least possible stress and disruption to the individual."

But as FOX6's research shows, nursing homes are still frequently calling 911 to deal with patients who have dementia. And more often than not, police handcuff the individuals and transport them away from their homes.

Gundermann says the behavioral crisis often happens because people with dementia can feel trapped can't verbalize how they're feeling.

"And you reach the point where you can't ignore them anymore because they're acting out. They're doing things you just can't ignore," Gundermann said.

"And they can’t communicate, and it just snowballs because nobody’s handling them properly," Mueller said.

Experts say if staff is caring for a patient properly, it should never get that bad in the first place. There are specific training methods staff members or caregivers can use to calm patients down to ensure a situation does not escalate.

"If you say you can care for people with dementia, you need to be able to care for people with dementia," Gundermann said.

Hlavacek says Wisconsin does not have a regulatory framework that defines dementia care. That means facilities can advertise that they specialize in dementia care, but they really might not have the necessary tools and training.

Mueller wants to see better training in more facilities in the future.

"I know that I can't change things for my mom," Mueller said. "I just hope it can change for someone else. That they don't have to go through what we had to go through."

After her mom was handcuffed and put in the back of a squad car, she was taken to a facility more than an hour away.

Brenda Mueller walks with her mother, Shannon Wittal, in the park.

"She didn't understand that they were trying to help her. She literally thought that she was in jail," Mueller said.

Mueller says her mom deserves better and shouldn't be punished just because she has dementia.

You might be wondering what the nursing homes and assisted living communities have to say about this issue.

The FOX6 Investigators tried to talk to industry leaders about the challenges they face, but nobody got back to us. We contacted the American Health Care Association, the Wisconsin Health Care Association and the Wisconsin Association of Homes and Services for the Aging.

Some of the caregivers we spoke to while reporting this story said care facilities can sometimes be in a tough spot. They legally have an obligation to keep all residents safe. If one resident is violent, they say they sometimes have no other choice than to call police.

Facilities say they can get in trouble for keeping someone who might have challenging behaviors, especially if they are violent. Some facilities say calling police is a last resort, while others say they never call police.

Police agencies say because of liability issues, they are often required to handcuff anyone being transported by squad car, no matter the age of the individual. Alzheimer's advocates say they could be transported by ambulance, with the police following behind, but that rarely happens given the extra expense.

If you or someone in your family is in need or resources or assistance for understanding Alzheimer's, you can learn more from the Alzheimer's Association Southeastern Wisconsin Chapter.

The organization has a 24/7 helpline: 800-272-3900.

You can also see the resources available on their website -- CLICK HERE.