Dr. Scott Atlas, Trump’s coronavirus adviser, resigns from post

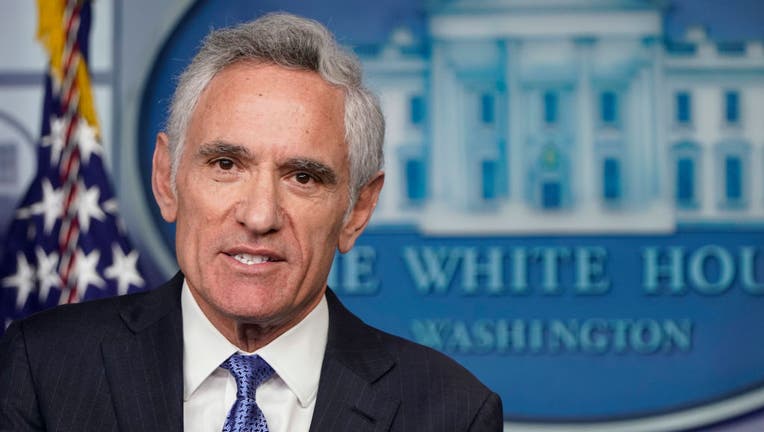

FILE - Dr. Scott Atlas, member of the White House's coronavirus task force, speaks at a news conference in the briefing room of the White House on Sept. 23, 2020.

WASHINGTON - President Donald Trump’s special adviser on the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Scott Atlas, formally resigned from his post on Monday, according to FOX News.

“I am writing to resign from my position as Special Advisor to the President of the United States,” Atlas said in a resignation letter obtained by FOX News. “I worked hard with a singular focus—to save lives and help Americans through this pandemic,” Atlas wrote, adding that he “always relied on the latest science and evidence, without any political consideration or influence.”

“As time went on, like all scientists and health policy scholars, I learned new information and synthesized the latest data from around the world, all in an effort to provide you with the best information to serve the greater public good,” Atlas wrote. “But, perhaps more than anything, my advice was always focused on minimizing all the harms from both the pandemic and the structural policies themselves, especially to the working class and the poor.”

“Indeed, I cannot think of a time where safeguarding science and the scientific debate is more urgent,” Atlas said.

Atlas had been criticized by health experts throughout his tenure for calling for a widespread reopening amid the surging pandemic and saying that lockdowns are “extremely harmful” to Americans. He listed among his accomplishments in his resignation letter that he “identified and illuminated early on the harms of prolonged lockdowns, including that they create massive physical health losses and psychological distress, destroy families and damage our children.”

RELATED: Questions arise as COVID-19 vaccine gets closer to reality

Atlas, the former chief of neuroradiology at Stanford University Medical Center and a fellow at Stanford’s conservative Hoover Institution, has no expertise in public health or infectious diseases.

Atlas joined the White House Coronavirus Task Force in August amid ongoing tensions between the president and Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation's top infectious diseases expert, and Dr. Deborah Birx, the task force's coordinator.

Many public health experts questioned Trump’s decision to bring Atlas, whose expertise is in magnetic resonance imaging and whose research has focused on factors impacting health care policy, on as a coronavirus adviser.

His controversial views also prompted Stanford to issue a statement distancing itself from the faculty member, saying Atlas "has expressed views that are inconsistent with the university’s approach in response to the pandemic."

“We support using masks, social distancing, and conducting surveillance and diagnostic testing,” the university said Nov. 16. “We also believe in the importance of strictly following the guidance of local and state health authorities.”

“I think he’s utterly unqualified to help lead a COVID response,” said Lawrence Gostin, a Georgetown University law professor who specializes in public health. “His medical degree isn’t even close to infectious diseases and public health and he has no experience in dealing with public health outbreaks.”

RELATED: ‘Great Barrington Declaration’ on COVID-19 ‘herd immunity’ draws criticism from experts

Gostin expressed concern that Trump was sidelining other doctors, including Birx and Fauci, because he had soured on their advice. “You want clear independent advice from people with long experience in fighting novel pandemics and he has none of those credentials,” Gostin said.

Atlas found himself in hot water earlier in November after tweeting to his nearly 90,000 followers suggesting that residents of Michigan should “rise up” against COVID-19 restrictions imposed by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer's administration.

“The only way this stops is if people rise up. You get what you accept. #FreedomMatters #StepUp,” the tweet, which was deleted by Twitter, read.

Atlas later tweeted that he wasn’t “talking at all about violence.”

“Hey. I NEVER was talking at all about violence. People vote, people peacefully protest. NEVER would I endorse or incite violence. NEVER,” Atlas tweeted.

After the U.S. surpassed 6 million COVID-19 cases in August, Atlas downplayed the risk of infections in young people and agreed with Gov. Ron DeSantis that college football needed to be played this year. Atlas described fit athletes as low-risk and said football “can be done safely” using social distancing in big stadiums.

Even with rigid guidelines and frequent testing which was implemented at the start of the college football season, universities have seen several outbreaks which have forced games to be postponed.

Atlas also downplayed the need to test people for COVID-19 who were asymptomatic.

“When you start a program of testing simply to detect positive cases among asymptomatic low-risk groups, the outcome from that is to close the schools," he said. "And the goal of testing is not to close things. The goal of testing is to protect the vulnerable while we open the schools and open the economy.”

In an April op-ed in The Hill, Atlas claimed that lockdowns may have prevented the development of “natural herd immunity.”

“In the absence of immunization, society needs circulation of the virus, assuming high-risk people can be isolated," he wrote. In television appearances, Atlas called on the nation to “get a grip" and argued that “there’s nothing wrong" with having low-risk people get infected, as long as the vulnerable are protected.

RELATED: U.S. could soon see 'surge upon a surge' in COVID cases, says Fauci

While the term “herd immunity” has been widely used in conversation about the novel coronavirus, evidence has emerged that the concept of immunity obtained through widespread infection of a population may not apply to COVID-19.

Epidemiologists define the herd immunity threshold for a given virus as the percentage of the population that must be immune to ensure that its introduction will not cause an outbreak. If enough people are immune, an infected person will likely come into contact only with people who are already immune rather than spreading the virus to someone who is susceptible.

A study published on July 11 by researchers at King’s College London found that antibodies detected in the human body which fight the coronavirus declined after a few weeks, leaving the possibility of herd immunity out of the question.

The implications of such a study engender the possibility that future waves of the novel coronavirus could return in seasons, according to researchers.

Herd immunity is usually discussed in the context of vaccination. For example, if 90% of the population (the herd) has received a chickenpox vaccine, the remaining 10% (often including people who cannot become vaccinated, like babies and the immunocompromised) will be protected from the introduction of a single person with chickenpox.

Even with two promising vaccines nearly ready to release to the public, doctors and health experts say that a majority of the population will need to get the inoculation in order for herd immunity to take hold.

Dr. Natasha Bhuyan, a family physician with One Medical, is optimistic about the current data related to the two vaccines, but says 60% to 80% of the population will need to get vaccinated for herd immunity to become viable.

"We still need a majority of people to get the vaccine in order to reach herd immunity, and I think that as long as we can show the public the vaccine is safe and the vaccine is effective, then I think people will voluntarily get the vaccine," said Bhuyan.

The Associated Press, FOX News, FOX 10 Phoenix and Austin Williams contributed to this report.