Fighting For Flint: Many remain resilient as city's water crisis evolves

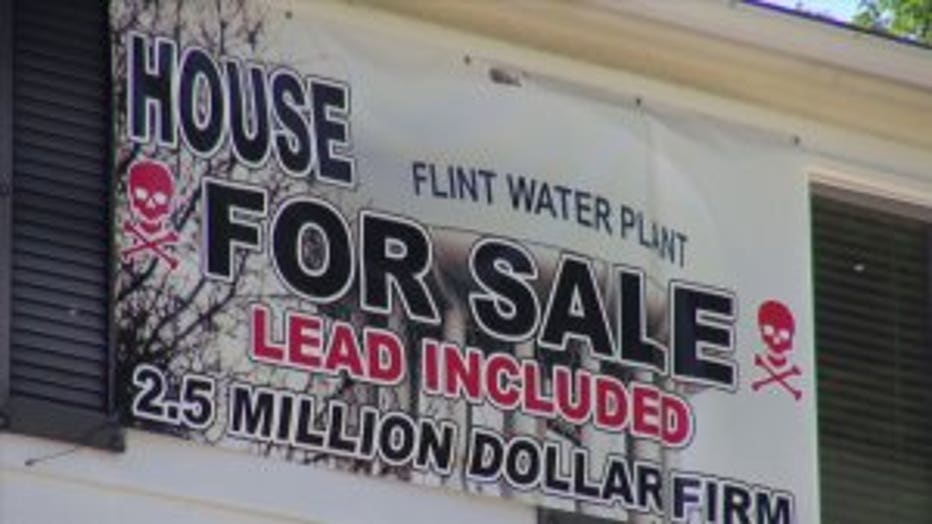

FLINT, Michigan -- Estelle Holley doesn't want to leave the home she's lived in since 1975, despite the sign she's hung out front. "House for Sale, Lead Included," it reads.

"It’s a protest sign. It’s not a for sale sign," Holley said during an interview on her front porch. "It’s 'hey, look at us people here who are left, us older people. We don’t want to go nowhere. Some of us can’t go nowhere.'"

Holley bought her home for $5,600 and, despite buying adjoining lots and making updates through the years, she said it's now worth $5,200. Like many Flint residents, she uses bottled water to brew her morning coffee, cook and bathe as the city's lead-water crisis evolves.

Estelle Holley

Twenty-seven months after missteps by government officials allowed lead to leech into the city's water supply, Flint remains in a state of emergency. Its 100,000 residents use a combination of bottled water, filters and the generosity of health care providers and charity organizations to deal with the crisis.

Flint Mayor Karen Weaver in late June rejected bids to replace the city's aging lead pipes, citing the high cost. While city officials come up with a new plan, the government is telling residents to run their water regularly in an effort to flush lead out of the system.

Clean Water for Flint

Filtered water deemed safe

Scientists have recently declared that Flint water was safe for everyone to drink, as long as it's filtered. The newest priority: make sure there's an operational filter in every home. In time, it will reduce the reliance on bottled water.

Yet a combination of factors -- inability to get to the state-run distribution locations, older faucets that don't work with the filters, and a lack of trust in official information -- mean a segment of Flint's population still needs bottles.

The American Red Cross makes weekly visits to 1,100 homes where people with mobility challenges live. The relief workers ask residents how many cases of water containing 24 bottles they need for the week, and they also check filters and cartridges.

Linda Giddings

At one stop, an apartment building on Flint's north side where many older people live, Red Cross worker Linda Giddings delivered water when she knocked on Mary Golden's door.

Golden, a 69-year-old resident of the building, thought she had a filter on her kitchen faucet until Giddings found otherwise. Installing one took five minutes, but didn't put Golden at ease.

Mary Golden

"Water's just not right for me," she said, when asked if she would switch to filtered tap water. "I'm not trusting the water no more."

Despite the setback, Giddings said people are gaining trust through the regular contact from charitable groups and relief workers.

"When I first started in February, I thought 'how can Flint recover from this?' I couldn’t imagine," she said. "I’m seeing more and more recovery every day."

Filtered water in Flint

Government to blame

The crisis began in April 2014, when cash-strapped Flint was under the control of a state-appointed emergency manager. City and state officials decided to stop buying water from nearby Detroit to save money and switch to Lake Huron water. But the pipeline, called the Karegnondi Water Authority, wouldn't be operational until 2017, so the Flint River was tapped as a temporary water source.

Detroit had been using the chemical phosphate to prevent Flint's lead pipes from leeching into the water. City and state officials didn't add the chemical to the Flint River water, and the lead problems quickly began.

Lead in water in Flint, Michigan

Despite cries from residents about the taste, smell and color, the State of Michigan for 18 months maintained that the water was safe to drink. Finally, in October 2015, after warnings from scientists and doctors, the state switched Flint back to Detroit water. Gov. Rick Snyder apologized and declared the state of emergency in January 2016.

Yet the lead levels still test high sporadically, and many fear the city's current pipes are too damaged to safely provide water to Flint homes again.

Milwaukee donations

Bridget Robinson, president of the National Pan Hellenic Council of Milwaukee, helped organize a local water drive for Flint earlier this year. Volunteers drove two truckloads of bottled water to Flint, along with $3,500 in donations.

"We really wanted to make an impact, and we felt like we did that," Robinson said. "This is a basic human need that was almost taken away from the residents of Flint."

Administrators with the Food Bank of Eastern Michigan said, as the national spotlight after Flint's emergency declaration waned, donations did, too. The most effective thing to donate to Flint is no longer cases of bottled water, they said.

"Donating money at this point is the best, easiest, fastest way to get help into Flint," said Kelly Belcher, a spokeswoman for the Food Bank.

As government officials consider potential solutions, most Flint residents now get their water and filters from five distribution sites around the city. The emergency effort has transitioned to other needs.

Lead-mitigating foods

Flint has few major grocery stores, so the Food Bank of Eastern Michigan is distributing food rich in Vitamin C, calcium and iron. The nutrients have been found to mitigate the lead levels in a person's body.

Food Bank of Eastern Michigan

"We had 120 cars come through," said Art Horton, holding a piece of paper where he'd tallied the number of people stopping at his north side church for peppers, potatoes and other vegetables. The church is one of the Food Bank's distribution partners.

"From my standpoint, Flint kind of needed this," he said. "This is something that'll bring us together."

How many will leave?

Those residents who can afford to leave the city are having to make the difficult decision whether to do so. Entrice Mitchell, a junior at the University of Michigan-Flint, is considering his future career in real estate.

Entrice Mitchell

"Nobody wants to leave their hometown, especially during something like this, leaving family behind and everything like that," Mitchell said during an interview at the YMCA of Greater Flint, where he works for the Safe Places after-school program.

While the program focuses on field trips and other fun activities, the YMCA has also provided kids with bottled water to take home.

Some Flint residents have become resigned to the situation, but many others have remained resilient through the crisis.

"That's just how we are," Mitchell said.

Holley, who supports the mayor's decision to reject the pipe bids because of their cost, has perhaps the best view of the crisis playing out in her city. From her backyard, she has a view of the Flint Water Plant's tower over the treetops.

"It's a constant reminder that the tower is full of lead," she said.

Lead pipes in Flint

To donate to Flint

Numerous charitable organizations have set up donation websites for Flint relief efforts, including:

United Way of Genessee County (Flint Water Fund)

Community Foundation of Greater Flint (Child Health and Development Fund)

Food Bank of Eastern Michigan (food and bottled water relief)