FOX6 Investigators: More help needed for mentally ill

MILWAUKEE -- When Jared Loughner shot Arizona Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords and killed six others in 2011, Heidi Yocum focused on the look in his eyes.

"You could see he was manic," Yocum said.

Yocum knows that look. Her son, Ron, has been suffering from bipolar disorder for years. Once known as "manic depression," it is a mental illness marked by dramatic mood swings and erratic behavior.

As a series of mass shootings continued to unfold throughout 2012, Heidi Yocum became increasingly concerned about her own son and how his struggles exemplify serious shortcomings in America's mental healthcare system. So she decided it was time to tell her son's story.

She wasn't the only one. Ron wanted to talk about it, too.

"Riding bikes was my passion as a child," he recalls.

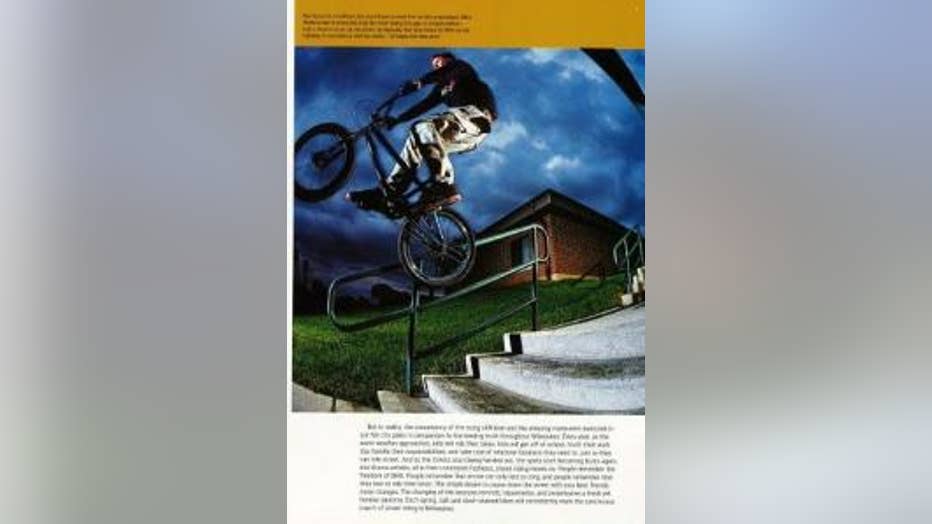

Ron Yocum is pictured performing a stunt in the October 2006 issue of Ride BMX magazine.

Most kids ride bicycles, but Ron Yocum practically lived on one. He is a BMX trick rider with friends who are professional freestyle stunt riders. Ron's fearless and aggressive style once landed him on the pages of Ride BMX Magazine, with a caption that describes him as a "madman."

But lately, Ron’s passion for riding has waned as he battles a mental illness that first manifested itself in 2006.

"I thought I was being awarded $93 billion to help the Katrina victims," he says.

So Ron got in his car and started driving. West. Even though New Orleans, of course, is south.

"I had no compass. I had my moral compass, but I had no compass to guide me," he explains.

"He just drove till he ran out of gas," his mom says.

Ron ended up near Monroe, Wisconsin, where he walked into a stranger’s house. He says he was searching for the Holy Grail.

"There was a girl inside and she ran away and she hid," Ron recalls. "And I left the house and was walking down the driveway and I was like,'Oh my god,' and realized, kind of, what I was doing. I just entered someone's house and I scared a girl," he says.

"I had a call from that sheriff," Ron's mom recalls. "He said, 'We have your son here. He is in Green County.' I am like, 'What?'"

The Green County sheriff recommended that Ron be placed on a Chapter 51 Commitment. It was his first ever stay in a mental hospital.

“It was as if someone either took a fist or a giant club and just smacked me right in the chest," Heidi says.

Ron was given a powerful cocktail of anti-psychotic medications, but after he was released, he stopped taking them. One year later, he tried to kill himself with a butcher knife.

"I took a knife to my throat and did it three times, just like this," Ron says, as he motions with his hands wrapped around an imaginary cleaver, jabbing it toward his neck.

"I mean it was like a horror movie," his mom recalls.

Once again, Ron was committed, medicated and released.

"It is like a revolving door with the hospital and court," Heidi says. "Back out, back in, back

Heidi Yocum felt compelled to share her son's story after a series of mass shootings in 2011 and 2012.

out, and uh, that is what is so exhausting."

Heidi says the mental healthcare system is confusing and alienating, especially to parents of an adult.

"It's fine if we can keep him here and we go 'Hey Ron, here are your meds,' and he is going along like a little soldier doing what he should. But no, he is saying he feels okay," Heidi says.

Ron admits he didn't like the medications, because of how they made him feel.

"Most of the time when they gave them to me I stopped right away, because I was either a zombie or zonked out the entire time or just super tired," Ron said.

"That is really tough," says Peter Hoeffel, Executive Director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness of Greater Milwaukee. "How do you get somebody treatment if they don't want it?"

Hoeffel says treatment is crucial to managing an illness of the brain.

Peter Hoeffel, Executive Director -- NAMI of Greater Milwaukee

"Heart disease untreated, that is a bad outcome," Hoeffel says. "Diabetes untreated, bad outcome. Cancer untreated, bad outcome. Mental illness untreated, it's going to be a bad outcome.'"

But Hoeffel says one of the greatest barriers to voluntary treatment is the stigma.

"Who wants to be considered crazy, psycho, a lunatic, a nut-job?" Hoeffel asks.

"It's just not regarded as a real illness," Heidi says. "They are treated like they are criminal, they have some control over this."

In fact, Heidi says the only time she’s ever been able to get her son treatment is after something bad happens.

In 2009, Ron drove circles around his parents yard in Kewskum, honking the horn and demanding to be let inside.

"I just heard a loud bang and I just thought, 'Oh, my god.' I thought he took the car through the front of the house," Heidi recalls.

Ron had kicked down the front door.

"For me to knock down that door was like taking down a kingdom," Ron says.

He was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct, then later found not guilty by reason of mental disease.

Ron Yocum is living on his own in a south side apartment in Milwaukee.

"I feel like that is the only time he has ever gotten into the hospital would be because of the police," Heidi says.

She does not necessarily think her son is a threat to the public. But he has been deemed a “substantial risk” before. And he is currently living, unsupervised, in a south side apartment.

"Who doesn't want to be independent?" Ron asks.

Heidi says the whole reason she is coming forward is to alert the public that there are always warning signs. She's just concerned the system isn't doing enough to treat the mentally ill before something goes wrong.

"We need to investigate what is happening with the mentally ill. How effective their treatment is, if they are being treated," Heidi said.

From the shooting of Congresswoman Gabby Giffords to the theater shootings in Colorado, the Sikh Temple shooting in Oak Creek and the massacre of children of Connecticut, mental illness is finally on America’s priority list.

"I am glad people are talking about mental health care," Hoeffel says.

But the increased attention is a double-edged sword.

"When you correlate with mental illness then everyone that has a mental health diagnosis has people thinking they are a potential threat or a danger. That's just not the case," Hoeffel says.

In fact, Hoeffel and Heidi Yocum have opposing views about why these mass shootings are occurring.

"The only common denominator in these school shootings - I mean mass shootings - is a gun," Hoeffel insists.

'It's not guns. That's not the problem. It is the person behind the gun," Heidi Yocum says.

But they both agree that the mental healthcare system needs improvement. And, incidentally, so does Ron.

"When you have people shooting up schools, our mental health system is not good enough," Ron declares. "That right there tells you that our mental health situation in this country and around the world is not good enough."

Earlier this month, Governor Walker pledged nearly $30 million to improve mental healthcare in the Badger state. That includes more than $10 million to expand community-based care programs for people just like Ron Yocum, who do not need to be held in a mental institution, but do need support to keep them on track as they transition back into community life.