'Half human, half robot:' Milwaukee teen 1st in state to receive robotic mobility device

MILWAUKEE -- FOX6 shares stories from all over. As it turned out, we found one at our station. Val Seiber has been an employee at FOX6 for several years. Her daughter, Trinity, has battled a rare birth injury her entire life. A new device is making a difference.

Trinity's story began on Aug. 29, 2001. Her mother recalled the day Trinity was born vividly.

"At the time of the birth, I'm noticing that it wasn't as smooth as my other kids," Val Seiber remembered. "After hours of trying to, you know, get this kid to be born. I hear this like. really faint cry."

Val Seiber delivered a healthy baby girl. However, she quickly realized something wasn't quite right.

"I noticed she wasn't able to stretch her arm. Like, her left," recalled Seiber.

The doctor soon revealed troubling news.

"This was the worst shoulder distortion case I've ever seen," Val Seiber remembered the physician telling her.

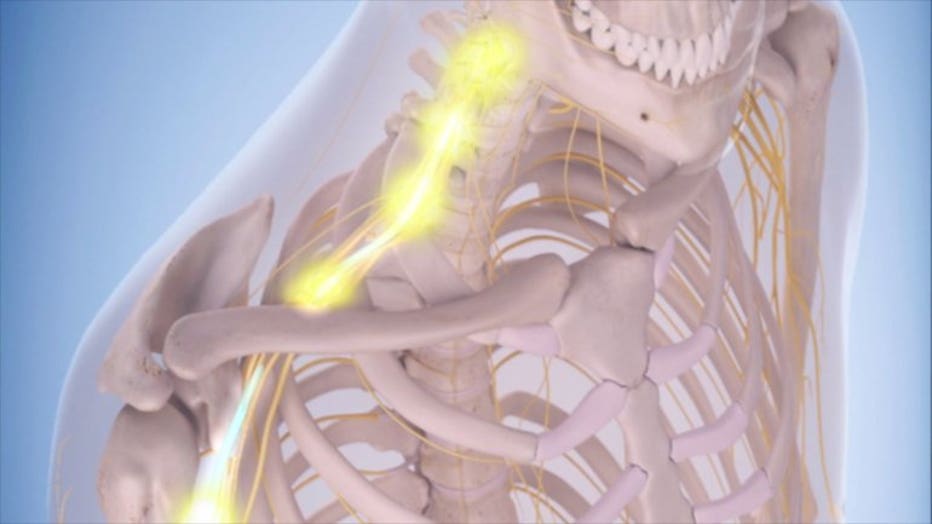

Trinity sustained a birth trauma called brachial plexus injury (BPI).

"The brachial plexus itself is a complex of nerves that branches off of the spinal cord. Around the level of the neck, as it continues to branch further, it controls motion and sensation of the arm," explained Dr. Alicia Zolkoske, a pediatric non-operative orthopedic physician with Children's Hospital of Wisconsin.

Dr. Zolkoske said there are several ways a BPI can occur, but one them is during birth.

"In the process of birth, it is possible for that neck area to be stretched and those nerves to be subsequently damaged," she said.

According to the United Brachial Plexus Network's website, statistics about BPI "vary widely." However, it's estimated two to five births out of every 1,000 sustain an injury to the brachial plexus.

Dr. Zolkoske said, typically, the injury heals on its own. However, a severe enough injury can have a devastating impact.

"In a larger injury, it's possible to have full loss of motor function and sensation of that arm," Dr. Zolkoske said.

While Dr. Zolkoske couldn't talk specifically about Trinity's injury, she said cases like hers are "incredibly rare."

Trinity said her injury left her with almost no arm movement.

"I lost maybe 90 percent of my mobility," Trinity said.

After learning about her daughter's injury, Val Seiber said she went into "fix mode."

"Can you fix this?" Seiber recalled asking the doctor.

In order to find a fix, they visited specialists in Wisconsin and Texas. Trinity would undergo six surgeries in nine years -- all away from home and family. Still, she never regained arm mobility.

"My emotions, obviously, were running high," Val Seiber said.

If you asked Trinity about the trips and the surgeries, she just remembered having a good time.

"I'm like, 'Ooo this is fun. I'm travelling. I don't know what's going on, but I'm going to have fun,'" she said about that time.

In fact, it's a positive outlook she still carries with her today. As a senior at Milwaukee Lutheran, Trinity walks the halls with confidence, but she admitted it wasn't always that way.

"I was just like, 'I don't know how to deal with this.' I hated how ugly I looked," she said.

"I didn't know what to do. I cried a lot," Val Seiber said about the time.

Trinity said the elementary and middle school years were the hardest.

"People were still like, excluding me from being in their cliques, or they didn't know how to process it," she recalled.

"She never complained. Never complained that she couldn't tie her shoe or comb her hair or put her own earrings on," Val Seiber said.

Instead, Trinity used her experience to find her voice.

"I'm gonna be just fine, whether people accept that or not. And, that's when I just stopped caring," she said.

She used her voice to change her narrative.

"She had been saying since she was 12 or 13 that she wanted a bionic limb," Val Seiber said.

Trinity discovered a robotics company called, Myomo. It is short for My Own Motion.

"I had I never heard of it -- for the record," Val Seiber laughed.

Trinity said she sent the company an email explaining her BPI and why she wanted the device. Myomo responded almost immediately.

"'Your daughter Trinity wrote us about this arm, and we want to come and meet her.' And I'm like, 'My daughter Trinity?!' She goes, 'Yeah!'" Val Seiber recalled about a phone call she received from the company.

Soon after the call, company officials came to Milwaukee and met with Trinity. They told her she was a good candidate for their robotic device.

"'We think that you're gonna be a great candidate,' and I'm like, 'I'm gonna be a great candidate?'" she remembered about the meeting.

Trinity was ready for the device called the MyoPro. The MyoPro is a robotic brace that gives arm mobility back to those who've lost it.

"It's most easily understood as sort of like Iron Man without the fireballs, because it is this thing that you wear on the outside of you and it moves only when you tell it to move. It's not stimulating you. You are sending command signals to it," explained Dr. Brandon Green, chief medical officer for Myomo.

Each brace is made specifically for the individual.

"We're refining the technology to turn into a fully custom fabricated arm brace that's made totally to spec to fit our patients perfectly," explained Dr. Green.

Dr. Green said the company's goal is to give its patients independence.

"We want them to be able to fully care for themselves in a way they couldn't do otherwise," he said.

"I gotta figure out a way to get it for her. This is her life," Val Seiber said about the MyoPro.

There was still one problem -- the cost.

"It's going to be an uphill battle for insurance for this device. Of course, they denied her the first time," Val Seiber said.

Once again, Trinity used her voice to make a difference. She wrote an appeals letter to her insurance company.

"I wrote them a letter saying, 'I really want this device and I want to get approved for it. Please help,'" Trinity said.

In November, Trinity received a letter saying she was approved for the device. In February, she became first teenager in Wisconsin to receive a MyoPro.

Her new arm takes practice.

"I've learned how to open and close my hand for the first time and lift my arm up. Things I could never do," Trinity said.

"The learning curve can be from a few weeks to a few months, so long as they stick with it," Dr. Green explained.

Trinity showed that she's starting to get the hang of it, but the pride she has wearing it came naturally.

"I'm like Cyborg. I'm half human, half robot. So, I'm like, 'Ooo, I'm going to enjoy this thing,'" she said.

Trinity said she's looking forward doing things she's been unable to do before.

"I always wanted to hug somebody normally. I know that's probably like, so random, but I was never able to hug people," she said.

She graduates high school in spring 2019. She's already been accepted to college. In the future, Trinity said she hopes to be a writer or editor.

"I see myself and my future, getting my master's degree in what I want to study, and I'm working for either BuzzFeed or New York Times, because that's always my dream," Trinity said.

"Everything she puts her mind to, she succeeds at it, and so the sky is the limit for her," Val Seiber said.

Trinity is ready to turn the page and start the next chapter of her life with her new arm.

"I don't want a pity party. I can enjoy my life even with this injury. It's not going to do anything to me," she said.

There's still so much of her story left to be written.