'It's essentially junk:' $7.5M bite mark settlement underscores national call for better forensic evidence

$7.5M bite mark settlement underscores national call for better forensic evidence

$7.5M bite mark settlement underscores national call for better forensic evidence

MILWAUKEE — He spent 23 years in prison for a crime he did not commit. Now, a Milwaukee man is finally getting justice for a conviction based on flawed evidence. His long-awaited day in court came amid a national effort to put forensic science on trial.

For decades, television shows have conditioned people to believe that people can pinpoint a criminal suspect with a shoe print, tire mark, or a single strand of hair, and they can do it with absolute certainty. However, the advent of DNA technology has proven that other forensic disciplines, once thought to be bulletproof, are susceptible. Those errors have put hundreds, if not thousands, of innocent people in prison.

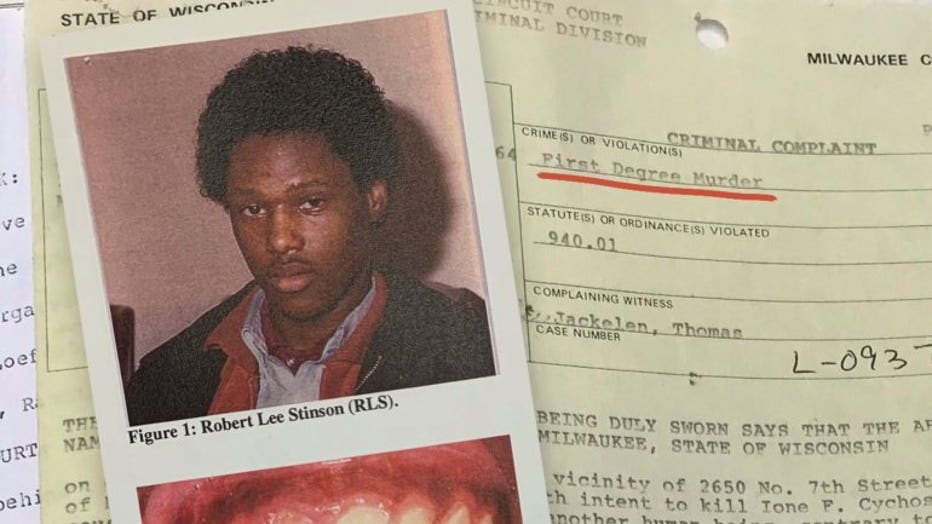

The conviction and exoneration of Robert Lee Stinson

When Robert Lee Stinson walked out of New Lisbon Correctional Center at the age of 44, his smile revealed a full set of teeth.

"It's been a long time. Twenty-three years. I was accused of something I didn't do," Stinson said when he was released in 2009.

Robert Lee Stinson leaves prison in 2009 after spending 23 years behind bars for a crime he did not commit.

More than two decades earlier, one of those teeth was missing, and that's all it took to convict him of murder.

"That was essentially the case. The whole case against Mr. Stinson," said Keith Findley, co-founder of the Center for Integrity in Forensic Sciences.

The location where investigators discovered the body of 63-year-old Iona Cychosz in 1984

In fall 1984, the body of 63-year-old Ione Cychosz was discovered in the backyard of a home near 7th and Center. She'd been raped and beaten to death. There were bite marks all over her skin.

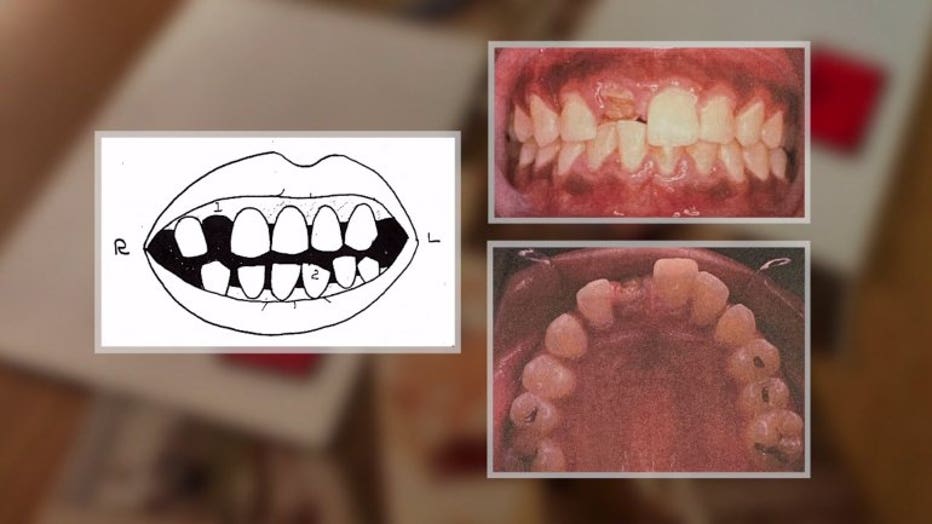

"Whoever left these bite marks had some irregular dentition," Findley explained.

Milwaukee police brought in a dental expert from Marquette University to examine the marks. Doctor L. Thomas Johnson helped police develop a sketch, which showed the killer would likely have a cracked or missing upper right tooth.

"It's a difficult job," Dr. Johnson said during a 2007 interview with FOX6 about forensic odontology.

Stinson lived just steps from the crime scene, and had a missing upper right tooth.

"The detectives closed this case after seeing Mr. Stinson," said Heather Lewis Donnell, Stinson's attorney since 2009.

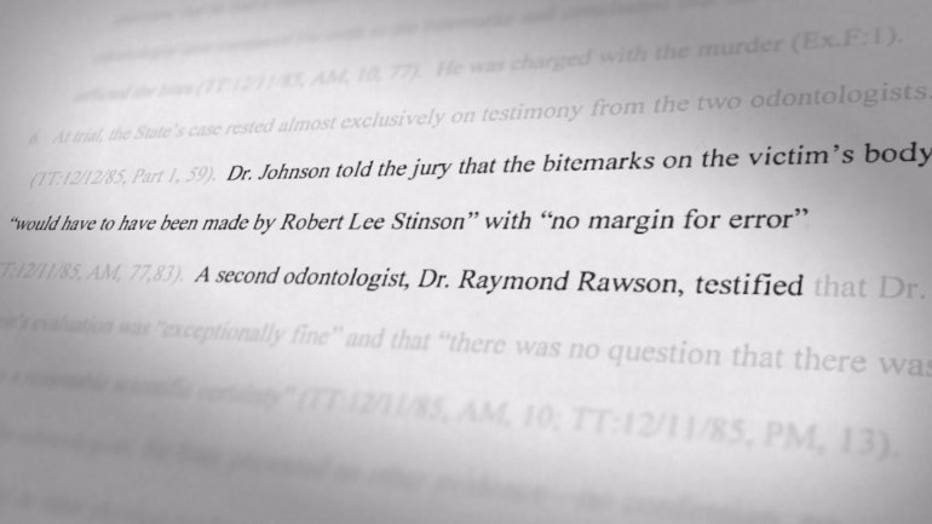

The jury never saw the sketch, which showed a different tooth missing than the one in Stinson's mouth, but they did hear Dr. Johnson say that the bite marks "had to have come" from Stinson. There was no margin for error. A second expert agreed.

"So they were saying, 'It has to be him,'" Lewis Donnell explained.

She said the level of certainty the dental experts relayed to the jury in 1985 was never supported by the science.

"That they had the ability, their science had the ability to say, 'It was this person, and only this person,'" Lewis Donnell said.

"It's really kind of preposterous," Findley said.

Twenty-three years would pass before Findley and the Wisconsin Innocence Project would prove the doctors were wrong.

"Did you ever think this would come?" a reporter asked Stinson after his 2009 release.

"No, I didn't. No, I didn't, but with the help of the Innocence Project -- came through," Stinson responded.

Robert Lee Stinson leave New Lisbon Correctional in 2009

DNA technology would eventually identify the real killer as Moses Price, but Findley said the bite mark analysis that put Stinson away instead was flawed from the start, and more recent research proves it.

"It's essentially junk," Findley said.

Questioning bite mark analysis

For more than 50 years, Dr. Johnson was a pioneer in the field of forensic odontology. He led a team of dentists that identified victims of the 1985 Midwest Airlines crash, and he helped police identify the remains of victims dismembered by serial killer Jeffery Dahmer.

Doctor L. Thomas Johnson

However, Findley said using bite marks to solve crimes is an entirely different process.

"Matching human remains is not the problem. Matching bite marks to a particular individual is a huge problem," Findley said.

Matching actual teeth to actual dental records is precise, but a growing body of research finds that bite marks left on the skin are unreliable, because skin is a terrible medium for retaining bite mark indentations.

"Because skin is malleable," Lewis Donnell explained.

"It stretches. It bloats. You bruise in funny patterns," Findley explained further. "And that's where the science has completely fallen apart."

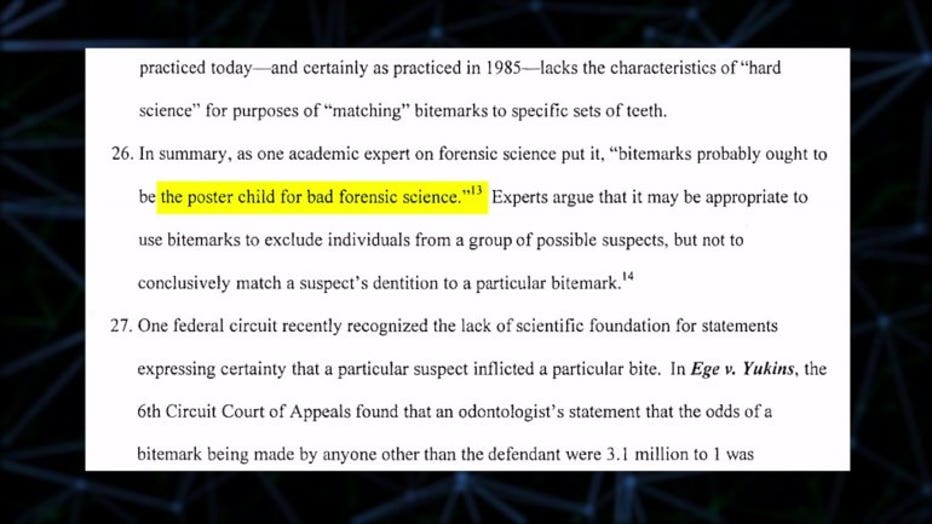

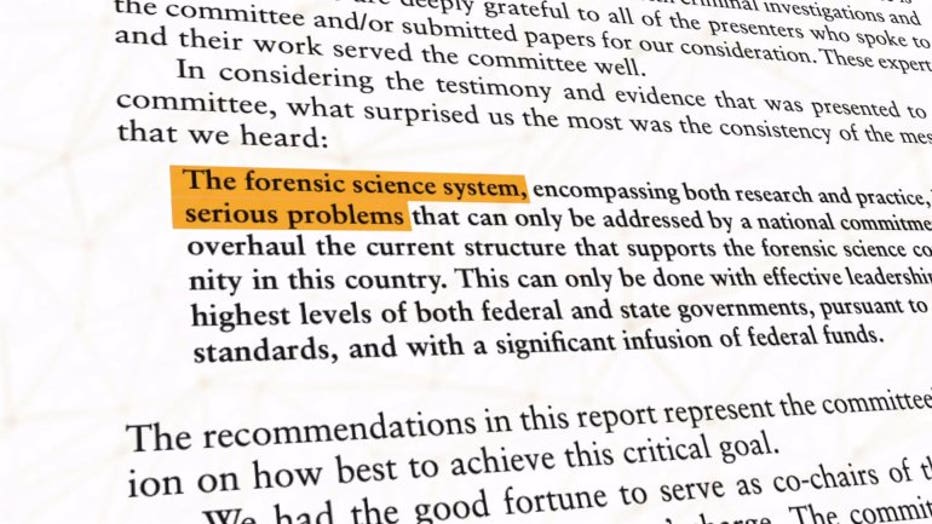

Study after study now questions the validity of bite mark analysis, with one expert calling it "the poster child for bad forensic science." A 2009 report by The National Academy of Sciences went further, citing "serious problems" across the entire "forensic science system," from fingerprints to firearms, and footwear to hair comparison.

Changing the face of forensic science

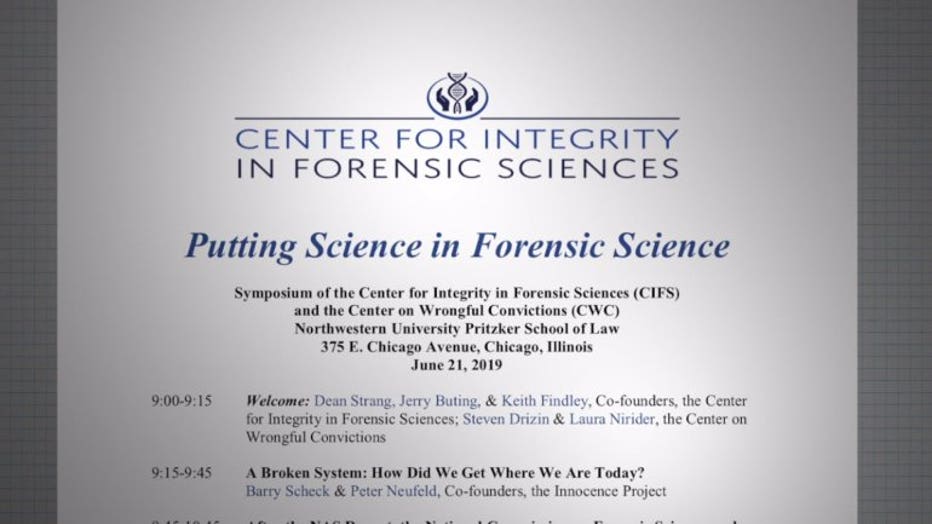

It was that government report and another that followed in 2016 that ultimately prompted Findley to join some of the nation's leading criminal defense experts in launching The Center for Integrity in Forensic Sciences. The first symposium was held in June at Northwestern University.

"This is one of our inaugural events," Findley said during the symposium. "We can't wait for the federal government to fix this."

"We want to ensure that the science we're producing is reliable and defendable," said Jennifer Naugle, deputy administrator of the Wisconsin State Crime Lab.

Naugle said she's on board with improving the science behind forensic science.

"'The only thing we're trying to do is seek the truth through science. That's it. That's really all it is," Naugle said.

She said a 2016 report by the Obama Administration unfairly lumped more reliable techniques used every day, like fingerprint and firearms analysis, with things like hair and bite mark analysis, which has been largely discredited.

Jennifer Naugle, Deputy Administrator of the Wisconsin Department of Justice's Division of Forensic Sciences, which operates 3 state crime laboratories in Milwaukee, Madison and Wausau.

"That's not something we would ever do at the Wisconsin State Crime Lab," Naugle said.

"We're not suggesting that all of the forensic disciplines are useless. They're not, but what we are suggesting is that they need to be improved," Findley said.

Dr. Johnson retired in 2013, but the following year, he published his final study on bite mark analysis. It concluded it is sometimes possible to narrow the source of a human bite mark to about 5% of the population. In other words, nowhere near a precise individual match. The FOX6 Investigators contacted Dr. Johnson by telephone, but he is 93 years old and unable to hear well. His wife declined an interview on his behalf.

Keith Findley, Co-founder of the Center for Integrity in Forensic Sciences

Now that Dr. Johnson is retired, there is only one board-certified forensic odontologist in Wisconsin -- Dr. Donald Simley in Madison. He declined an interview for this story because Dr. Johnson is a close personal friend and mentor. Dr. Simley has not testified in a bite mark case since 2003. While he believes there is still value in this type of evidence, he said police are better off swabbing a bite mark for DNA than trying to match a suspect's teeth.

Across the country, the Innocence Project has exonerated more than 160 people who were convicted with flawed forensic evidence, including 10 because of bite marks.

"This evidence is dreadful," said Jennifer Mnookin, UCLA School of Law, during the symposium.

Yet, bite mark evidence is still admissible in more states, including Wisconsin, where, ironically, Stinson's case still serves as the legal precedent.

"Even though Stinson has now been conclusively exonerated, and the bite mark evidence in his case has been shown to be false," Findley said.

Robert Lee Stinson seeks justice in federal court

Ten years after Stinson's release, his federal civil rights case against the dentists and the City of Milwaukee finally went to trial.

Robert Lee Stinson listens during testimony in his federal civil rights trial. Sketch by Jeff Darrow.

"There was a lot of powerful and moving testimony," Lewis Donnell said.

Attorney Heather Lewis Donnell shows a physical mold of Stinson's teeth used by Dr. Johnson and Milwaukee Police to link him to the bite marks on the victim's body in 1985.

Just before the case went to the jury, they settled out of court. The City of Milwaukee will pay Stinson $7.5 million. Stinson's attorney said the remaining terms of the settlement -- including any amount other defendants have agreed to pay -- will remain confidential.

"We're just really grateful that this is how it ended, and that Mr. Stinson got some measure of justice after all he's been through," said Lewis Donnell.

Thirty-four years later, Stinson can finally move on, but the injustice he endured is sure to leave a mark.