Neighbors sue Concordia University over bluff damage

Concordia being sued over bluff restoration project

Concordia being sued over bluff restoration project

MEQUON (WITI) -- Lakefront homeowners are suing Concordia University in Mequon. They say the school's much-celebrated bluff restoration project is damaging their property and threatening their homes.

Since it was completed in 2008, Concordia's $12 million bluff stabilization project has received national and international acclaim as a marvel of civil engineering. But some neighbors who live south of campus say the massive rock structure that's holding Concordia's bluffs in place is doing irreparable damage to theirs.

Concordia University's bluff restoration took 8 years to plan, 3 years to complete and cost roughly $12-million.

The cause is hard to see on a calm summer day, when the waves are gentle. But with wind and time, the coastal waters of Lake Michigan pack a destructive punch.

Patrick Ferry knows that power well. He is President of Concordia University, which for years had been losing valuable land to lakefront erosion.

"Mother nature is a very powerful force," Ferry says. "And we needed to have a very strong remedy in order to be successful."

Computer modeling produced by the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute simulates 44 years of relentless coastal erosion in Ozaukee County just south of the Concordia campus. And according to researchers, the bluffs at Concordia were especially unstable. So in 2005, the university embarked on a monumental engineering project to stem the tide.

The bluff stabilization took eight years to plan, three years to complete, and cost roughly $12 million dollars.

"We not only found a way to abate the erosion," Ferry says, "but it really transformed our campus in a remarkable way."

Dr. Patrick Ferry, President of Concordia University

The project eased the slope of the bluffs and gave the school both a physical and aesthetic connection to the lake it had lacked since moving to the Mequon location in 1983.

That includes a staircase and switchback path that are popular with fitness buffs, trails that attract birdwatchers, and a small public beach.

"It's great for Concordia, and it's also been great for our community. And I think it's a model for how to work on this," Ferry says."

But it is the project's most prominent feature that appears to be its most controversial -- 100,000 tons of stone that line of half-mile of Lake Michigan shoreline. The massive stone revetment serves as a sort of retaining wall. And neighbors now say that wall is causing them serious problems.

"It was over engineered," says Phil Koepke, who lives five houses south of Concordia. "They put the revetment 80 feet out into the lake. Into the public lake. They didn't need to do that."

Phil Koepke lives five houses south of Concordia. He is suing the university for damage to his bluffs.

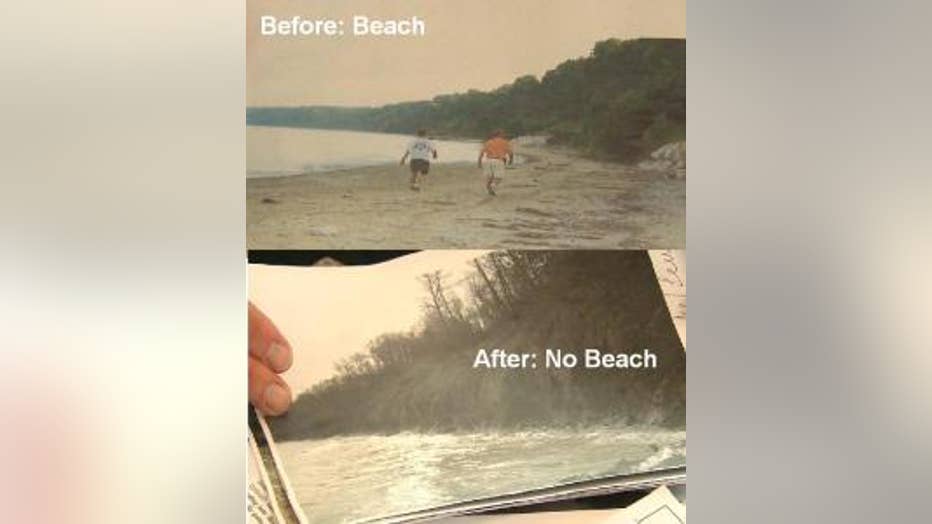

Koepke says the stone wall is preventing the normal flow of sediment from north to south, starving neighboring properties of sand.

"We had a vast sand beach... before they started their construction project," Koepke says.

Today, the beach is gone.

"And now the bluff is beginning to take a direct hit from the wave action," Koepke says.

Before the project, Koepke says he could literally walk a path from his house high above the lake down to the public beach. Now, that path ends at a cliff.

"Once you lose the toe of your bluff things start accelerating very quickly," he says.

Before (2005) and after (2008) photos of Koepke property.

Elizabeth Lewis lives next door to Koepke, four houses south of Concordia.

"We used to have a nice, flat back yard," Lewis says.

Now, her yard is tumbling down the bluff. She says she's lost about 15 feet of land since the Concordia project was finished. In fact, her bluff is crumbling so rapidly, she's concerned her house may soon go with it.

"We noticed first, small things like, 'Oh, where did the beach go?' And then there were pieces of the bluff blowing away and then, boom, huge chunks of the bluff falling away," Lewis says.

Both Lewis and Koepke say they warned Concordia this was going to happen.

In 2005, they and other neighbors urged the Mequon Common Council to proceed with caution.

" assured us many, many times during those presentations that there would be no effect on the neighbors," Koepke recalls.

The project was approved by the state DNR and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

"We absolutely spent tons and tons of time making sure this project would not have any adverse or accelerated impact on the erosion of any properties adjacent to Concordia," Ferry says.

But in 2008, Koepke says Concordia's own engineer witnessed the damage for himself.

"Came back after taking pictures and said, 'I am not surprised by your problem. We have experienced changes in the beach in this particular area. I will recommend a settlement being given to you by Concordia.'" Koepke says.

Instead, the university told them the damage was due to natural causes.

So Koepke and Lewis filed a lawsuit, accusing Concordia of "disregarding" their concerns and "causing significant damage" to their bluffs and shorelines.

"We can't replace this property," Koepke says, while staring out over his sagging lakeside bluff. "Once it washes away, it's gone."

Dr. Ferry declined to comment on the pending lawsuit, but he maintains the bluff stabilization project has been a huge success.

"This has been as transformational as anything in my 23 years on this campus," he says.

But it's the transformation in her backyard that worries Lewis. She's a motivational speaker who teaches clients stress management and forgiveness. Tools that may come in handy in this battle over the bluffs.

"They are our neighbors," Lewis says. "We want the best for them as well as ourselves. And what's going on right now is not the best for anybody."

The firm that designed and built the project - Smith Group JJR - sent FOX6 News a brief, written statement that says shoreline erosion is "naturally occurring and constant" and that the Concordia bluff restoration was "careful, well-planned" and approved by state and federal regulators.

Click here to read the full statement.