'Terrorist threat' exposes mental health treatment gap

WAUKESHA, Wis. - A Milwaukee man accused of threatening mass violence in Waukesha says he never actually planned to hurt anyone. He suffers from bipolar disorder but refuses to take medication.

That's why his family came to FOX6 Investigator Bryan Polcyn.

Prosecutors in two states have charged Timothy Hoeller time and time again with making vague threats to shoot up a social security office, a county courthouse and a university campus.

His family says he belongs in treatment, but in Wisconsin, mental health experts say, it's easier to send someone to jail.

The 61-year-old defendant insists he is not a threat to anyone.

Donald and Bernadette Hoeller say their son is no "terrorist." He's mentally ill but refuses to get treatment.

"First of all, I don't have any guns," Hoeller told a Waukesha County judge in 2018 after he was charged with disorderly conduct for referring to mass shootings during a dispute with his employer.

"He doesn’t have a gun," said Donald Hoeller, his father.

"He has no access to a gun," said Mary Hoeller, his sister. "He doesn’t want a gun."

But for a man without guns, he can't seem to stop writing and talking about them.

In February, prosecutors charged Tim Hoeller with making "terrorist threats" against Carroll University. The private school in Waukesha with roughly 2,800 students hired Hoeller in January 2017 to teach a physics course. The university fired him three months later in the middle of the semester after students complained.

SIGN UP TODAY: Get daily headlines, breaking news emails from FOX6 News

"Do you believe your son is dangerous?" asked FOX6 Investigator Bryan Polcyn.

"No," said Don Hoeller.

"No," agreed his mother, Bernadette Hoeller. "I don't."

Don and Bernadette Hoeller have had a front-row seat to their son's mental health struggles for more than 40 years.

"He would yak, yak, yak and never make any sense," Don said.

"He's not a bad person," his mother said. "He’s got morals and everything. It’s just that he’s ill!"

Tim Hoeller completed two master's degrees after his diagnosis of a serious mental illness more than 40 years ago.

The youngest of six, they say Tim was first diagnosed with a serious mental illness in the late 1970s after graduating from Nicolet High School in Glendale. He went on to get two master’s degrees, but while millions of Americans like him live productive lives with the help of medication, Tim refuses to take it.

"We mention medicine to him," Mary said. "We mention it all the time! But he just blows up and walks away."

Instead, she says Tim spends his days and nights obsessing over perceived slights and flooding the courts with frivolous lawsuits.

"He sues everybody," his father told FOX6 Investigator Bryan Polcyn. "You’ll probably get sued."

Tim shares his legal theories with anyone who will listen. In May, just before a hearing in his felony threat case, Hoeller spotted Polcyn waiting outside the courtroom. Without any introduction, Hoeller began speaking.

FREE DOWNLOAD: Get breaking news alerts in the FOX6 News app for iOS or Android

"They should know that my hearing is only a status," he said. "However, I filed a federal lawsuit against this courthouse 'cause they failed to make an investigation within one year of the previous case."

Unprompted, he continued, "They'd have to agree to be sued in federal court because the district attorney never investigated within a year. I caught them on that."

Moments later, Hoeller's attorney pulled him away.

Erin Cartwright-Weinstein, Lake County, Illinois clerk of circuit court, reported Hoeller to law enforcement in 2018 after receiving a letter that described mass shootings in the context of his complaint about an electronic filing fee.

"We have a list of people we struggle with," said Erin Cartwright-Weinstein, the clerk of circuit court in Lake County, Illinois. "He was on that list."

When Weinstein was elected in 2016, she said, Hoeller - who lived in Illinois at the time - was so well known to judges and court staff, he'd been barred from filing documents without advance court permission.

"Because he was overloading the court's docket," she said.

Then she said he took his behavior too far.

"He started getting more aggressive in the office and scaring the clerks," she said.

In February 2018, Hoeller sent her a letter that immediately grabbed her attention.

"Probably the most concerning letter I've ever received," she said.

According to a Lake County sheriff's report, the letter addressed Hoeller's unhappiness with his experiences with electronic filing. At one point, he wrote, "I am not responsible for the safety and security of the occupants of this building." He added, "Someone will go on a shooting spree as you walk outside your building to go home someday."

The source of his frustration? A $75 filing fee.

Cartwright said she had no choice but to call police.

"If we see something, we have to say something," she said.

The same day Hoeller sent that letter to Cartwright, he also sent a fax to Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker and Catherine Jorgens, a lawyer for Carroll University. The eight-page letter complained that the school's decision to terminate his teaching contract was "wrongful" and left him "indefinitely" out of work.

He then warned the school would be liable "if someone comes onto campus and performs a school shooting."

Nine days earlier, Nikolas Cruz killed 17 people at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

In the fax to Governor Walker and others, Hoeller referred to "the shooter in Florida" as "a hero to me."

"Where do we go except the criminal justice system?" Cartwright-Weinstein said.

Over the past 10 years, Tim Hoeller has lived in Illinois and Wisconsin. He's been in and out of jails and psychiatric hospitals in both states, including a six-month commitment in 2013.

"They gave him some medicine to take home," his father recalled. "When that ran out? Same old, same old."

In 2012, Hoeller was criminally charged with threatening to "gun down employees" of a Social Security office in Barrington, Illinois. The case was later dismissed after the court found him not competent for trial.

In 2018, he was convicted of making threats to "bust out in gun violence" at the Lake County Courthouse in Waukegan, Illinois. The court sentenced him to two years of probation.

Also in 2018, Waukesha prosecutors charged him with disorderly conduct for stirring up fears at Carroll University. He pleaded "no contest" and received a six-month jail sentence.

Since then, Hoeller has lived in a Milwaukee apartment that his sister describes as disorganized with "papers everywhere." He has continued to flood the courts with lawsuits, letters and appeals, and in February (2022), police say, he wrote another letter complaining about his ongoing feud with his former employer, hinting that someone would "shoot innocent people" on the Carroll University campus.

Carroll University contracted with Hoeller in 2017 to teach a physics course, then terminated the contract before the semester was complete. Hoeller is now accused of making "terrorist threats" against his former employer.

The letter prompted the university to issue a campus-wide alert warning students to be on the lookout for Hoeller. Soon, he would face a new felony charge – making terrorist threats and causing a public panic.

"Words have meanings," said Kevin Costello, a Waukesha court commissioner who denied Hoeller's attempt to have the case thrown out. Hoeller's attorney, Paul Crawford, argued his client never made an overt threat to harm anyone.

"We have, at best, alarming language," said Crawford.

It's true that Hoeller has never made a direct threat to perform a mass shooting himself. Instead, he hints at the risk of such things happening in circumstances similar to his.

"He always talks about other people doing these things," his father said. "And that's bad. I understand that."

"It creates fear," said Cartwright-Weinstein.

The proliferation of mass shootings across America has heightened public sensitivity to the red flags of potential mass violence.

"Mass shootings are a very emotional and powerful thing in our culture right now," said Dr. Tony Thrasher, medical director of crisis services for Milwaukee County Mental Health.

Dr. Thrasher believes too much emphasis has been placed on those with mental illness.

"Mental illness has always been a common scapegoat," he said.

While research shows people with bipolar disorder are nearly three times more likely to commit violence than those without it, most individuals with a serious mental illness are not dangerous.

"He’s never punched anybody or even slapped anybody," Hoeller's father said.

In fact, they are more likely to be victims of violence.

Dr. Tony Thrasher, medical director of crisis services for Milwaukee County Mental Health, says the threshold for an involuntary civil commitment in Wisconsin is higher than arresting someone for a criminal charge.

"This is really more of an issue of how we handle people who may need treatment but don't want treatment," Dr. Thrasher said.

"I just wish there was a way you could impress upon them or force them, somehow, to take meds," said Tim's mother, Bernadette.

"Because when he’s on meds, he’s wonderful," his sister added.

Dr. Thrasher says getting adults in Wisconsin into treatment against their will is difficult, in part, because the legal standard is high.

"The threshold for having your rights taken away civilly due to a mental illness is much higher than that of a criminal charge," he said.

It's also difficult because there aren't enough places to put them.

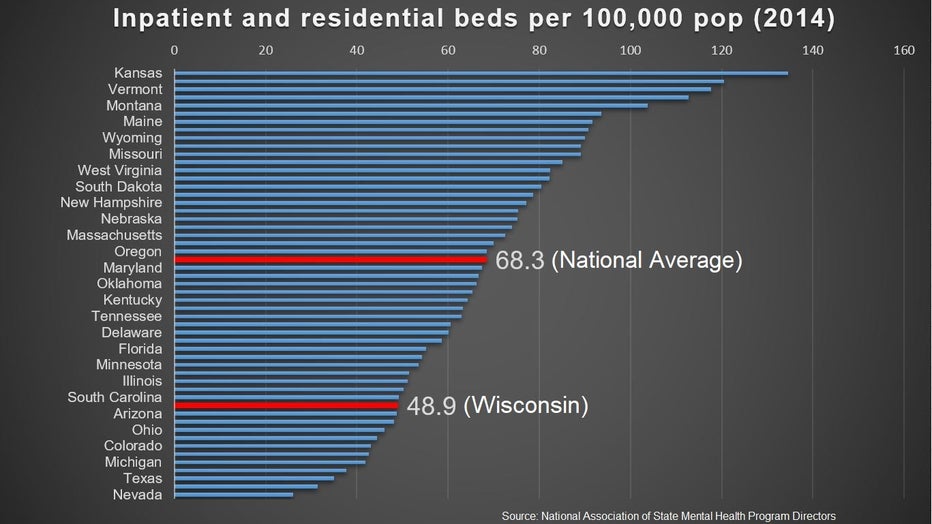

Of the more than 218,000 Wisconsinites with a serious mental illness, less than 2% receive inpatient or residential care.

In 2014, Wisconsin had fewer than 50 psychiatric beds for every 100,000 residents. That's one of the lowest rates in the country.

"What we end up with is people who are really sick in jail, instead of in the hospital," said Dominic Sisti, associate professor of medical ethics and the University of Pennsylvania. "And that, to me, is a huge stain on our moral integrity as a society."

Sisti wrote a 2015 article with a provocative title – "Bring back the asylum."

"Deinstitutionalization, as it played out, was a failure in a lot of ways," he said. "And it left people who really need care out."

Starting with President Kennedy's signature in 1963, hundreds of thousands of psychiatric patients were released from state mental hospitals on the promise that outpatient clinics would replace them.

Sisti says the promise was a good one. Funding for thousands of outpatient clinics would allow those with mental illnesses to get treatment while they lived in the community, instead of locking them up in state institutions where terrible conditions had been exposed.

But Sisti says the funding needed to make outpatient treatment work never materialized, and private hospitals today are either full or too expensive.

"Jails end up being our overflow for these places," he said. "And they shouldn’t be because they make people worse."

"I think when it came to the asylum era, we threw the baby out with the bathwater," said Dr. Thrasher.

"Now they overdid it," said Donald Hoeller. "Swung too far to the other end."

"I don’t know how to fix it," said Mary Hoeller. "We don’t know how to fix it. We just wish he’d get a commitment again."

Wisconsin does have a path for private citizens to petition the county for an involuntary commitment, but Tim's father says the family tried that.

"You put them in, two to three days, they walk out on you and you can’t stop them legally," he said.

Beyond that, it's up to police to initiate and for the courts to determine if Timothy Hoeller is merely sick… or dangerous.

"We are one of the few states remaining where law enforcement is the primary contact point," Dr. Thrasher said.

"We’ve got to fix the system!" Mary Hoeller said.

In May, a civil court judge issued a 10-year restraining order against Hoeller, blocking him from having any continued contact with Carroll University, including the university's legal counsel and members of the school administration and faculty.

As for the pending felony case, Hoeller's attorney, Paul Crawford, requested a competency evaluation in June 2022, then asked the court to withdraw from the case in July. In August, attorneys for the state and defense reported that two doctors are independently recommending Tim Hoeller be involuntarily committed and medicated until he's well enough for trial.

However, Hoeller objects to their findings and plans to contest those findings in a hearing on Thursday, Oct. 6. Crawford agreed to remain Hoeller's attorney for that hearing. In the meantime, Hoeller remains free on $1,000 cash bail.

FOX6 Investigators did not speak to Tim Hoeller directly for this story. His family cautioned against what they suggested would be unproductive conversations. We consulted with Al Tompkins, a journalism ethics expert at the non-profit Poynter Institute. Tompkins advised that a person with an untreated and serious mental illness might be confused by a reporter's questions and may not have a full understanding of the risks associated with talking to a reporter while a criminal case is pending.

Instead of directly contacting Hoeller, we reached out to Crawford, his criminal court attorney. Crawford said that, due to his own ethical obligations, he could not answer specific questions about the pending case. However, he did respond to two, more generalized questions:

Question: Why do you believe individuals with serious mental health issues often wind up in criminal court?

Answer: "The behavior of individuals with serious mental health issues oftentimes causes an uncomfortable reaction to the people who observe it. Frequently, when confronted with an individual who exhibits bizarre or irrational behavior, our first instinct is to contact law enforcement. The role of law enforcement isn't always to work through those issues, and far too often these calls result in an arrest. This reactionary response, with law enforcement involved, on many occasions, but admittedly not always, results in arrest and initiates the process for the criminal justice system and can result in charges."

Question: What do you think can or should be done to improve access to mental health treatment for those who currently end up in the criminal justice pipeline?

Answer: "An additional step in the screening or intake process, when someone is clearly exhibiting mental health issues, to divert them from the criminal justice system to mental health treatment would be ideal. Understanding funding can be an issue for treatment courts, these specialized courts still result in the individual being part of the system. Ideally, this additional step in the screening process can help identify and prevent appropriate candidates from entering the criminal justice system in the first place and instead put them in the direction of proper care and treatment."