'The potential is great:' Public DNA databases are solving violent crimes (and raising privacy concerns)

Public DNA databases are solving violent crimes (and raising privacy concerns)

Public DNA databases are solving violent crimes (and raising privacy concerns)

PORT WASHINGTON — Your DNA could help catch rapists and killers, but should police be able to use it? The FOX6 Investigators found the emerging investigative technique is cracking cold cases across the country, and privacy advocates are worried.

For millions of Americans, genealogy is a hobby. For Cindy Stirmel, it is a path to finding her biological father.

"I look at this, honestly, at least, you know, 10 times a day," Stirmel said as she scrolled through vital records stored on the laptop computer in her West Allis apartment.

"So you're into this," said FOX6 Investigator Bryan Polcyn.

"Oh yeah," she said, chuckling at the understatement.

Five years ago, Stirmel bought her first DNA testing kit, which turned a vial of her saliva into a genetic fingerprint that could be compared with millions of others around the world.

"If they're already a match to me, it will automatically show up," Stirmel said, showing a screen full of "matches" in her private account on Ancestry.com.

Thanks to the testing companies' DNA matching software, she's built a tree of relatives she never knew she had.

"All because of one of these kits?" Polcyn asked.

"All because of one of these kits," Stirmel said.

Companies like Ancestry, 23andMe, MyHeritage, and Family Tree have collected DNA from more than 27 million people, and that data is solving more than just family mysteries.

"We're solving crimes," said Jim Johnson, Ozaukee County sheriff.

On October 22, 2019, Ozaukee County Sheriff Jim Johnson announced the 1984 murder of Traci Hammerberg had been solved thanks to forensic genealogy

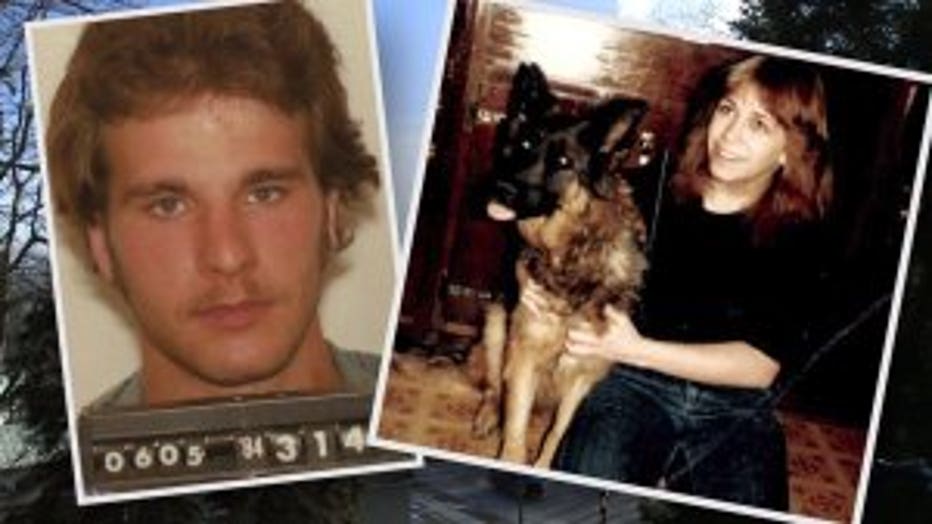

Philip Cross, Traci Hammerberg

In October, Johnson squared up to a podium and announced that his agency, in cooperation with the FBI, Wisconsin Department of Justice, and a third-party laboratory, had identified Philip Cross as the man who raped and killed 18-year-old Traci Hammerberg in 1984.

It was news that Hammerberg's younger sister, Jennifer McDonald, waited 35 years to hear.

"Somebody continued to care. I want to say a big thank you to them for never giving up on her," McDonald said.

Sarah Zastro-Arkens is the Wisconsin Crime Lab analyst who made the final comparison confirming that Cross's DNA matched the evidence found on Hammerberg's body.

"It was a good day here at the lab. There were some high fives. My heart was racing," Zastrow-Arkens said.

But it's how investigators got to Cross in the first place that has the criminal justice system buzzing, and privacy advocates nervous.

"It's amazing," Johnson said.

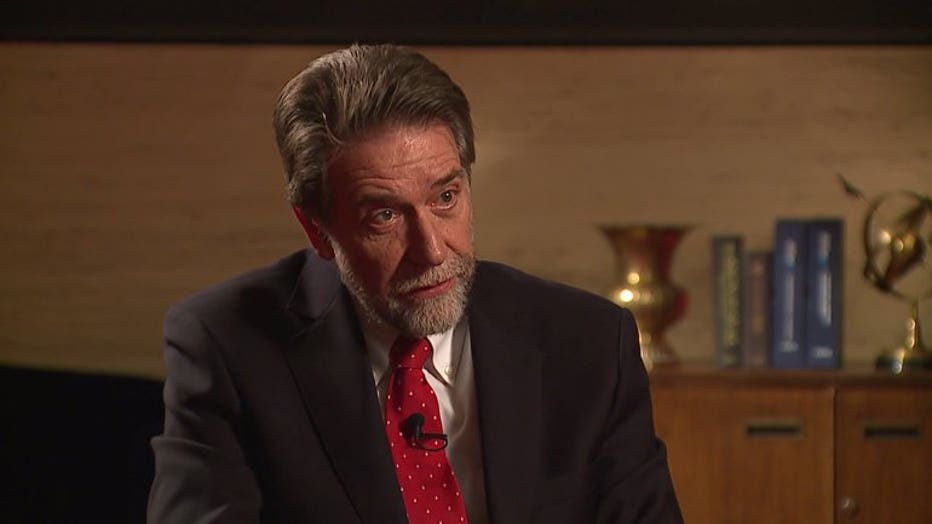

Attorney Ray Dall'Osto says consumer DNA should have privacy protections to prevent misuse and abuse.

"We have to have some kind of protections," said Attorney Ray Dall'Osto. "Right now, we have none."

From coast to coast, law enforcement agencies are catching rapists and killers with the help of forensic genetic genealogy.

"It's still in the very early stages, but the potential is great," Dall'Osto said.

It's a technique pioneered by CeCe Moore, who turned a hobby into a ground-breaking profession.

"Became very quickly considered an expert because there were no experts," Moore said.

CeCe Moore pioneered the forensic genetic genealogy technique but says she was initially hesitant to share it with law enforcement out of "responsibility" to the millions of DNA consumers she had encouraged to upload DNA information for genealogical

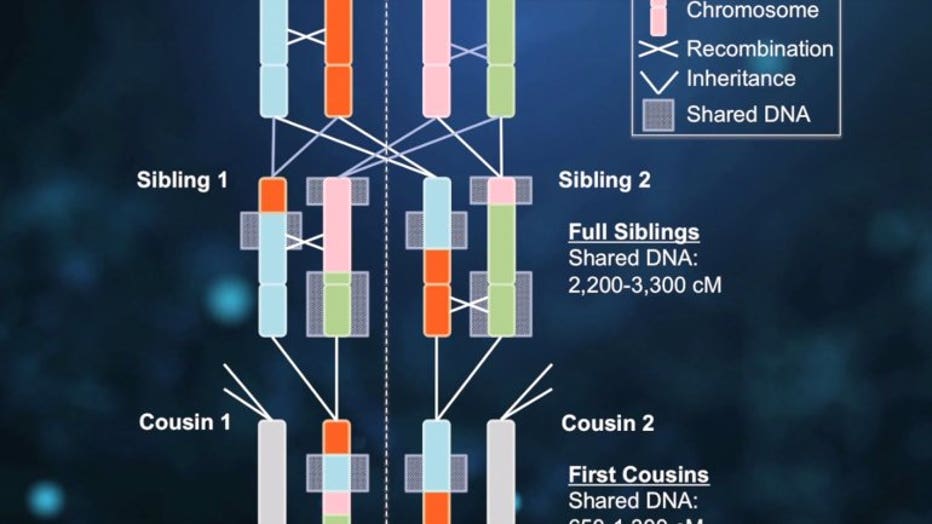

Because DNA recombines from generation to generation, Moore said people who are related share blocks of DNA. She found a way to measure how much.

"I think it's 232 centimorgans, would be a second cousin's," Johnson said.

So police can use crime-scene DNA to search for relatives, and then, traditional genealogy to drill down to a suspect.

"We had to build out the tree, and then come back down again to look for anybody that would be considered a second cousin," Johnson said.

"There's wide divide in my community about whether this is an appropriate use of what we created," Moore said.

Until recently, police could only compare crime scene evidence to a database of convicted criminals called "CODIS."

"Only available to law enforcement," Polcyn said.

"Which is only available to law enforcement," Dall'Osto said.

"The DNA from Traci's suspect has been in there for years with no hits," Johnson said.

Now, store-bought tests have created massive databases of DNA from people who may never have committed a crime.

"What privacy protections are out there?" Dall'Osto said.

Dall'Osto is a criminal defense attorney and former legal director for the Wisconsin ACLU.

"This is you. This is your code, and the potential uses of that and misuses are great," Dall'Osto said.

The three largest DNA testing companies -- Ancestry, 23andMe, and MyHeritage -- say they will not share your data with law enforcement without a court order, while Family Tree DNA does allow police to have access if they ask permission first.

"There is no national standard," Dall'Osto said.

DNA recombines from generation to generation, leaving predictable amounts of "shared" DNA. That allows investigators to search a DNA database for relatives of an unknown suspect.

But more than a million customers of those companies have voluntarily uploaded their genetic information to another public database called GEDmatch to help with family research, and many had no idea police could use it, too.

"Not that we are trying to hide anyone who is a murderer, and a rapist, and should be apprehended, but what is the other potential? Shouldn't there be some regulation of this?" Dall'Osto said.

Earlier this year, GEDmatch changed its privacy policy to require that users opt-in if they want to give police access to their DNA, and the U.S. Department of Justice issued an interim policy that calls for reasonable privacy protections.

"It's better than no policy," Dall'Osto said.

"We're going to have a bumpy road going forward," Moore said.

"There's people that go both ways on it," Stirmel said.

Stirmel didn't get into genealogy to solve violent crimes.

"I'm here to find my family," Stirmel said.

But if police use her DNA to take a killer off the street, she figures all the better.

"For me personally, I wouldn't have a problem with it, because I have nothing to hide," Stirmel said.

The U.S. Department of Justice's interim policy on forensic genetic genealogy took effect on Nov. 1.

It lays out requirements for use of the technique -- most notably, that it can only be used in cases involving violent crimes like rape and homicide. It must have a local prosecutor's approval, and the information obtained cannot be used to determine health-related information.

The Department of Justice hopes to have a permanent policy in place sometime in 2020.

Earlier this year, a judge in Florida approved a search warrant giving police access to the full GED-Match database even though 90% of those users have not opted-in for law enforcement access.

Some DNA policy experts say that could be a game-changer in favor of forensic genealogy.