'What's wrong with my son?' Wisconsin rejects $4 test for rare, terminal disease

WISCONSIN RAPIDS — They thought their newborn baby was perfect, but a Wisconsin couple soon discovered he had a deadly disease. The FOX6 Investigators found the state of Wisconsin has, so far, declined to test newborns for the rare condition that killed their son.

When Collin Cushman was born on December 19, 2010, he was perfectly healthy. There was no sign of any terminal illness.

It's a genetic disorder known as Krabbe disease, which affects fewer than 1 in 100,000 children. Experts say early detection is critical to an affected child's chances of survival. Other states are adding newborn screening for Krabbe, but state officials in Wisconsin say there's not enough research to justify the four-dollar test.

The first day of parenthood is all about nerves, and relief.

"What do I do?!" Kevin Cushman recalls thinking, the day his son, Collin, was born. "'I don't know what to do!' I said, 'Is he OK?' And she said, 'He's perfect.'"

"And he was," said Judy Cushman, Collin's mom. "I mean, he was perfect when he was born. He was perfect."

Kevin always wanted a boy, but he and Judy agreed that's not what mattered most.

"Just as long as they're healthy," he said.

"As long as the child is healthy," Judy repeated. "And I had every reason to believe that my child was going to be healthy."

Ten years later, they can hardly remember those first few months when Collin was just like any other baby.

In home videos the Cushmans recorded in early 2011, Collin was able to hold his own bottle and smile. Symptoms would not surface until he reached 8 to 9 months.

What they will never forget is when everything changed.

"His whole body is stiff," Kevin says in a home video recorded when Collin was about 9 months old.

That's when Collin's muscles began to get tight. His reactions slowed. He became incessantly irritable. And, eventually, his face fell into an open-mouthed expression that would never go away.

Around 9 months of age, Collin's muscles stiffened and he became incessantly irritable, needing to be constantly held. Experts say the signs are often mistaken for colic, but are even more persistent and severe.

"I remember holding Collin with tears, going, 'What's wrong with my son?'" Kevin said.

The answer was worse than they'd ever imagined. Collin had a rare, genetic disorder known as Krabbe disease. That meant he was going to die at an early age.

"You know, your dreams are shattered," Kevin said.

First, there would be years of tube feedings, vibration machines, and round-the-clock care.

"It was... challenging," Kevin said.

Collin was lucky enough to survive until the age of 9. Most Krabbe children die before they turn 2.

"It's horrifying," said Dr. Barbara Burton, a specialist in genetic medicine at Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago.

She says Krabbe disease is a form of leukodystrophy that causes the body's nerves to degenerate.

"You lose the coating on the nerve fibers that transmit signals from one nerve cell to another," said Dr. Burton.

"So as the myelin was destroyed, slowly lost more and more abilities," his father said.

The disease affects fewer than one in every 100,000 newborns -- perhaps even as few as one in 400,000 -- and there is no cure. There is, however, a way to treat the disease and improve a child's chance of living a longer, more functional life.

"We would've had a totally different boy," Judy said.

The trouble is, the treatment -- a hematopoietic stem cell transplant, or HSCT -- only works to treat Krabbe if it's done within a baby's first 30 days alive. Most parents have no idea their child even has the disease until symptoms surface months later.

"By the time the symptoms show themselves, it's too late," Kevin said. "There's no hope."

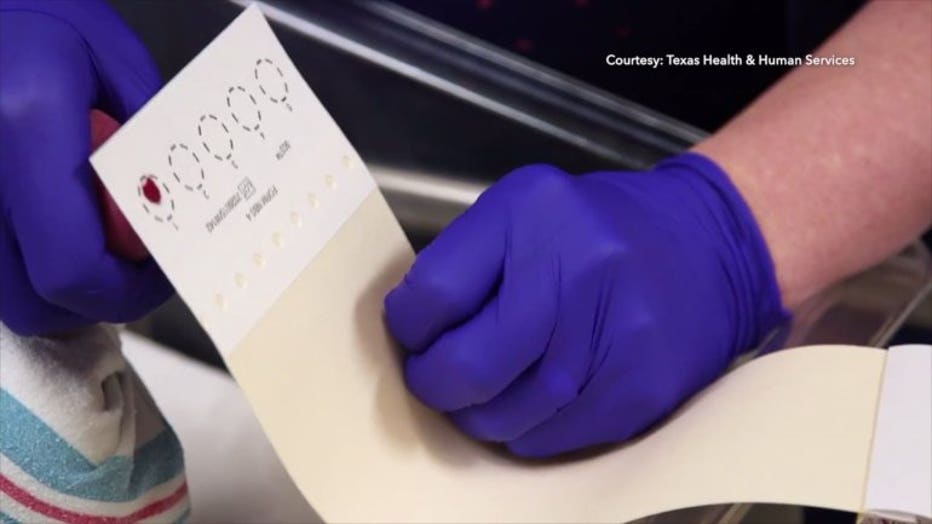

Wisconsin already screens newborns for 48 different disorders, most through a heel prick blood test administered before a child leaves the hospital.

In 2018, Dr. Burton joined a team of experts in publishing guidelines that recommend newborns be screened for Krabbe before they leave the hospital. All 50 states already have programs to test newborns for a host of other disorders by pricking the child's heel to draw blood and placing that blood inside circles on a laboratory test card.

"It might just be another circle that they fill out," Kevin Cushman said.

At least six states now test for Krabbe in newborns, while five others have passed laws allowing for it. Those states are in varying stages of development for the testing protocol. In 2015, Wisconsin rejected a nomination for Krabbe to be added to th

New York was the first state to start testing for Krabbe in 2006, followed by Missouri, Kentucky, Ohio, Tennessee, and Illinois. At least five more states are now working to implement the screening, but so far, Wisconsin has rejected efforts to add Krabbe to the 48 disorders tested for at birth, in part, because there's not enough long-term research to prove the treatment works.

"I hear that argument over and over again, and I think it's ridiculous because the same thing could be said for almost any other condition for which we do newborn screening," said Dr. Burton.

Five years ago, the Cushmans nominated Krabbe disease for inclusion in Wisconsin's newborn screening program, but Chuck Warzecha, deputy administrator for the Wisconsin Division of Public Health, said the test results in too many "false positives."

"There are some risks and emotional impacts on the family when they get that false positive," said Warzecha.

The state's 2015 review of Krabbe testing relied on research that's now more than 10 years old and Dr. Burton says newer testing is more accurate.

"Our technology has gotten much better," said Dr. Burton.

In addition, some Krabbe patients who have gotten transplants are living longer more functional lives.

"We know if it gets detected early that it's treatable," said Senator Patrick Testin, a Stevens Point Republican. He's working on a bill to require Krabbe testing in Wisconsin -- as long as the cost doesn't derail his plan.

State Senator Patrick Testin (R-Stevens Point) is working on a bill to include Krabbe disease in the list of disorders included in the state's newborn screening program.

"Yeah, that might be a potential roadblock," Testin said.

In 2015, the state said Krabbe screening would cost an extra $300,000 a year, or roughly $4 per test.

"For $4, why wouldn't you?" Judy asked.

"Try to imagine yourself in the shoes of a family who finds out their child has Krabbe disease, and then talk about whether $4 per baby is worth it," Dr. Burton said.

"No child should have to go through this," Kevin said.

Even if Collin had been tested for Krabbe at birth, the Cushmans can't say for sure if they would have gone through with a transplant. The procedure is risky, and some children don't survive.

"I would've given anything to have had that choice," Kevin said. "Even if it didn't change the outcome. As a father, I think I would've felt at least a little more comfortable knowing that I literally did everything I could to save my child."

Of course, the risk of an early death without the transplant is 100%.

On Jan. 6, 2019 -- seven years to the day after Collin was diagnosed -- his father held him for the last time.

Collin Cushman died on Jan. 6th, 2019. His parents vow to keep fighting for Krabbe screening "for as long as it takes."

"I was gonna hold him as long as it took," he said. "If it took two days before he passed, I was not gonna let go of him."

It's not how the Cushmans imagined things when they welcomed their firstborn child into the world, but they couldn't have asked for a better goodbye.

"Surrounded by family," said Kevin Cushman. "It was perfect."

Krabbe is not on the federal government's recommended list of disorders for newborn screening, but two similar disorders are, including Pompe disease. The state of Wisconsin recently completed a pilot project for Pompe, and they are considering whether to test for it permanently. If they do, DHS says adding Krabbe testing after that would be less expensive than it would have been in the past, because the equipment and training would be similar.

For now, Krabbe is not part of Wisconsin's newborn screening program. The Cushmans intend to keep pushing until it is.

Krabbe is a recessive genetic disorder that is passed down, like blue eyes or attached earlobes. A child is only at risk if both parents are carriers of the mutated gene that causes Krabbe. Even then, there's only a 25% chance the child will get the Krabbe gene from both of them.

Parents can be tested before having a baby to determine if they are carriers of the disease, but -- because it is so rare -- most soon-to-be parents know nothing about it.

Even after Collin was diagnosed, the Cushmans chose to have a second child. This time, they knew there was a 25% risk the second child would have Krabbe. Judy Cushman called it "the worst lottery ever."

Fortunately for them, Kendra Cushman was born without the disease. Five years later, she is symptom free.