Wisconsin AI-powered Flock cameras are tracking where you drive

AI-powered cameras tracking where you drive

Hundreds of AI-powered cameras are tracking vehicles in Wisconsin. Police call it a "game changer." Privacy advocates call it "mass surveillance."

GRAFTON, Wis. - Hundreds of artificial intelligence-powered (AI) cameras in Wisconsin are keeping track of where you drive, and police can search the data without a warrant.

It is a new form of government surveillance rapidly spreading across the Badger State. Police call the license plate reading cameras a "game changer." Privacy advocates call it "mass surveillance."

Garrett Langley says it's the beginning of the end of crime.

"I want crime to stop!" Langley exclaimed during an interview with FOX6 Investigators.

Langley is the founder and CEO of Flock Safety, a surveillance technology company that is rapidly expanding its national footprint.

Garrett Langley, founder and CEO of Flock Safety (via Zoom)

"Do you envision a future with a Flock camera on every street corner?" asked FOX6 Investigator Bryan Polcyn.

"I envision that," Langley affirmed. "And I envision an America where crime no longer exists."

Flock AI safety camera questions answered

FOX6's Bryan Polcyn answers your questions about Flock AI safety cameras. They're keeping track of where you drive, and police can search the data without a warrant.

Always watching

"Thaaaat is, um, a little crazy, I think?" said Jay Stanley with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). "You'd be recording all of us, everywhere, all the time."

The ACLU's privacy and technology policy analyst warned in 2022 that Flock is building a mass surveillance system "unlike any seen before in American life."

"It can reveal what kind of political events you go to, medical things, financial things, whether you’re a faithful spouse, how often you go to bars," Stanley said.

SIGN UP TODAY: Get daily headlines, breaking news emails from FOX6 News

But Langley said Flock never collects personally identifying information.

"We don’t track people," Langley said. "We track cars."

Flock is born

Langley is an electrical engineer who graduated from Georgia Tech in 2009. As doorbell cameras exploded in popularity, Langley found they often were not enough to catch neighborhood thieves because they often could not provide a specific lead.

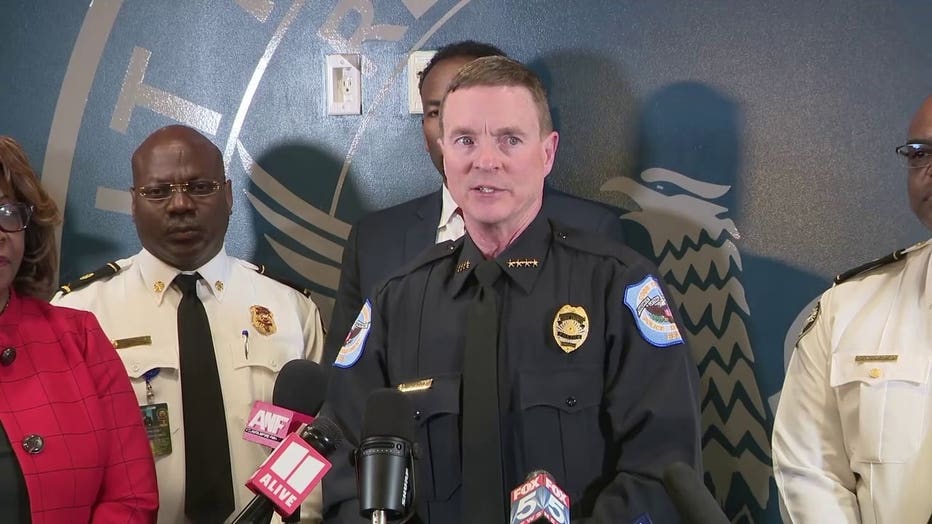

"We don’t need a video," said Cobb County Georgia Police Chief Stuart VanHoozer. "We need a tag number."

So in 2017, Langley teamed up with some of his former Georgia Tech classmates to build a camera that could read license plates – and VanHoozer was one of his first customers. When his agency captured an active shooter in May, VanHoozer publicly credited Flock for the assist.

Cobb County, Georgia, Police Chief Stuart VanHoozer was one of Flock's first customers

"This is the single best tool we have ever seen in 33 years," VanHoozer said.

Just six years after Langley founded the company, it is already valued at $3.5 billion, and police departments across the country are lining up to join the Flock.

"This is a game changer," said Grafton Police Chief Jeff Caponera, one of the first chiefs in Wisconsin to adopt Flock technology, which happened in January 2021. "Like, overnight, cameras started just popping up everywhere."

Rapid growth in Wisconsin

Two years later, a FOX6 investigation finds at least 219 Flock cameras are actively scanning traffic in the Milwaukee area with plans for nearly a hundred more in the coming months. Grafton has 10 of them.

"We’re interrupting more crimes than we ever have," Caponera said.

FREE DOWNLOAD: Get breaking news alerts in the FOX6 News app for iOS or Android

West Allis has 21 Flock cameras.

"We obviously can’t have officers all over the city all the time," said West Allis Deputy Chief Robert Fletcher.

Waukesha has 28, with three more waiting to be installed.

This is an early version of the "deployment map" prepared for Waukesha Police Department by Flock Safety's sales team. It consists of 31 cameras, 28 of which have seen been installed.

"I think we owe it to the community to leverage as much technology as we can," said Waukesha Police Lt. David Daily.

Of the 36 largest police departments in southeast Wisconsin, our investigation finds 75% already have Flock cameras or have contracts to install them soon.

Departments without cameras can still access Flock's database of more than 1 billion vehicles captured every month, as long as they sign a Memorandum of Understanding establishing the terms and conditions.

"I have the ability to network with over 17,000 different cameras across the nation," Caponera said.

"And that allows for mass searches across the country," Stanley said.

"That’s powerful," Polcyn said.

"Yes," Fletcher replied.

More than ALPR

Flock says its cameras do not use facial recognition and they don't measure speed. One of their primary uses is comparing vehicles that pass the cameras to hot lists of stolen, wanted or missing vehicles. Anytime a hot-listed vehicle passes by a Flock camera, police received an alert.

"Every point of ingress and egress in my village is covered," Caponera said.

West Allis police said that leads to quicker stolen car recoveries. Sometimes, it leads to vehicle pursuits that prevent car thieves from coming into the city to commit more crimes.

"It keeps them from being in our city," Fletcher said.

"You run ‘em out of town," Polcyn replied.

"Correct," Fletcher answered.

Flock's Falcon cameras run on solar power and use cellular networks to send data to cloud-based servers maintained by Flock.

Unlike other automated license plate readers, Langley says Flock cameras are solar-powered, require little infrastructure and cost less upfront. Instead of buying the cameras, police lease them for $2,500 to $3,000 per camera, per year. That becomes an annual taxpayer expense that won't go away as long as they keep the cameras.

"You've got to commit year to year to year," Caponera said.

But Langley said it is not the camera that sets Flock apart.

"It’s the computer vision and AI on top of that," Langley said.

Machine-learning software detects more than two dozen other attributes of each vehicle that an eyewitness might remember. Flock even trademarked the term they use to describe it – the Vehicle Fingerprint.

"Does it have damage?" Langley offers as an example. "Does it have after-market tires?"

"They're picking up bumper stickers," Caponera added. "They’re picking up roof racks."

"The make, the model, the color," Langley continued.

All of that data is transmitted over cellular networks to Flock's cloud-based servers, where it is stored in a centralized database that officers can search right from a squad car laptop.

Caponera said that means even if a criminal removes the license plate, police can still track them.

"I can narrow my search down to a white Toyota Prius with no plates," Caponera said.

Flock solves crimes

Police say it is working. Germantown police received an alert that a car they wanted for retail thefts was in Grafton, prompting a chase that led to two arrests.

Mequon police arrested 25-year-old Shane T. Davis, Junior, for identity theft after a series of Flock camera hits showed him coming and going from the nursing home where the elderly victim lived.

In Beaver Dam, police say 17-year-old Dylan Lenz stabbed a girl he had just met on social media, then ran her down with his car as she tried to get away. Witnesses described a dark blue 2009 Pontiac Vibe leaving the scene. Even in the dark, a nearby Flock camera captured a photo that led police directly to the suspect's front door.

This Flock capture in Beaver Dam helped police track down a 17-year-old now charged with attempted homicide for running his vehicle over a girl he'd just met through social media.

"It’s a very powerful AI tool," Caponera said.

Potential for abuse

But it does not just track criminals.

When FOX6 Investigator Bryan Polcyn asked Grafton police to search his own license plate in the system, they found 23 photographs from multiple cameras over the past 30 days. In other words, Polcyn's whereabouts were tracked in a police database even though he was never the suspect in any crime.

Police say they only look at the data if there's a reason connected to crime, but privacy advocates say it's a concern.

"It's something that creates a lot of potential for abuse," Stanley said.

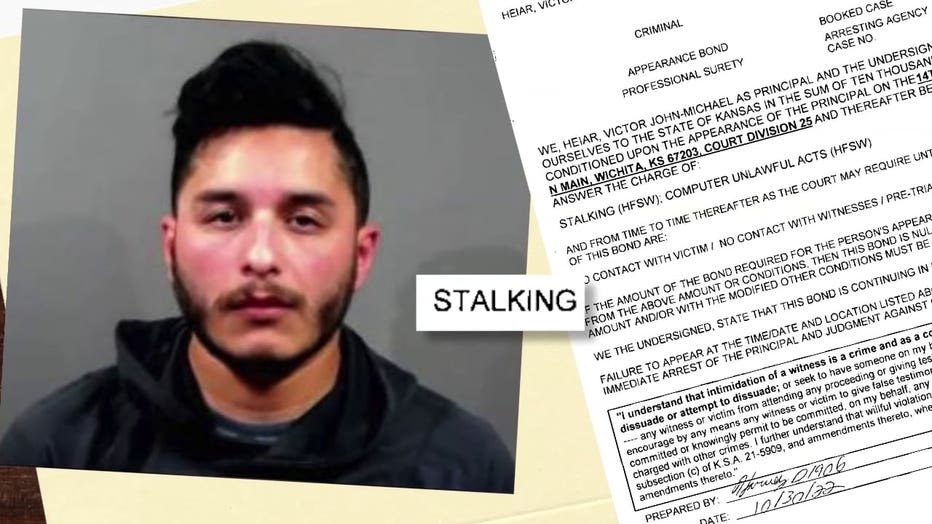

Last fall, a police officer in the small community of Kechi, Kansas, tapped into Wichita's Flock database to stalk the mother of his children.

Text messages show Victor Heiar then grilled the woman over where she'd been:

Heiar: "Where did you take my kids this morning? Around 10."

Victim: "How would you know we weren't home?"

Heiar: "You were spotted on Meridian [Avenue]."

Victim: "Spotted, by whom?"

Heiar: "Does it matter?"

It was not until after the victim complained that police reviewed the officer's use of the Flock system.

Former Kechi, Kansas, Police Officer Victor Heiar was convicted of stalking his estranged wife by accessing Wichita's Flock network in the fall of 2022

Langley says Heiar was caught because of a built-in safeguard that requires officers to enter a reason code every time they search the system. When Heiar was searching for his wife's car, he simply entered generic terms like "test" or "investigation" as the reason.

"He was apprehended," Langley said. "He was fired immediately, and he was criminally charged for breaking the law."

Those searches are saved forever and police can audit them at any time.

"And they can assess, ‘Is there anything bad happening?’" Langley said.

Waukesha police say they do periodic audits.

"We routinely monitor that to ensure the system isn’t being abused," Lt. Daily said.

But West Allis police do not.

"We don’t have regular audits currently set up," said Deputy Chief Fletcher.

Langley acknowledges there is risk.

"I'm of the mind that data is largely a liability, not an asset," Langley said.

Data retention

By default, Flock deletes vehicle data after 30 days. Waukesha police are paying extra to keep their data 121 days – four times longer than the standard policy. There is no law that prevents them from keeping it longer. In fact, Wisconsin has no laws on data retention for automated license plate reading cameras at all.

"It's happening so fast that the law hasn’t had time to keep up," Stanley said.

Meanwhile, the Flock is only growing. But how far will it go?

"We don't want a camera everywhere," VanHoozer said.

The Georgia police chief said there comes a point when you can have too much of a good thing.

"And then it’s wasteful and probably borders on concerning," VanHoozer said.

"I don’t think that a camera on every street corner is necessary," Lt. Daily said.

"I don’t believe that’s realistic," Fletcher said.

After all, it's hard to maintain a private life when the cameras are always watching.

"I don’t want to live in a police state," VanHoozer said. "And I am the police."

Existing Flock cameras

If you're wondering where you can see a map of Wisconsin's existing Flock cameras, you can't. The Wisconsin Department of Justice says it does not keep track of Flock cameras at all. While some individual police departments did send FOX6 Investigators maps or lists of camera locations, others – including Milwaukee, Franklin and Brookfield – blacked out the current and proposed locations. Brookfield's city attorney wrote that disclosing Flock camera locations could give a "strategic advantage to those who wish to engage in criminal behavior," by allowing them to avoid routes with Flock cameras on them.

What questions do you have?

We know the use of Flock cameras may have prompted questions by you. We would like to hear your questions, concerns, and feedback on the use of this artificial intelligence-based system. FOX6 Investigators plans to answer some of those questions in a FOX LOCAL exclusive to be released on Friday, Aug. 4.