Record-breaking Arctic ozone hole closed itself up, and it may have nothing to do with lockdowns

NEW YORK -- A rare and very large hole that opened up in the ozone layer over the Arctic in early April has now healed itself, scientists say.

According to the Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service (CAMS), it was an "unprecedented" hole and scientists announced its closure on Thursday. On Twitter, the organization responded to a follower, saying the current pandemic and a reduction in pollution due to lockdowns around the world were likely not the cause for the ozone hole closing.

"Actually, COVID19 and the associated lockdowns probably had nothing to do with this. It's been driven by an unusually strong and long-lived polar vortex, and isn't related to air quality changes," the tweet read.

The group said the ozone hole was a result of a polar vortex, but closed when that vortex split. What makes this unusual is polar vortexes are typically weaker in the Arctic, meaning the conditions needed for the strong ozone depletion that occurred in early April don't normally occur. Thus, CAMS said it was "unprecedented."

The depletion was so severe over the Arctic this year that most of the ozone at an altitude of 11 miles was depleted.

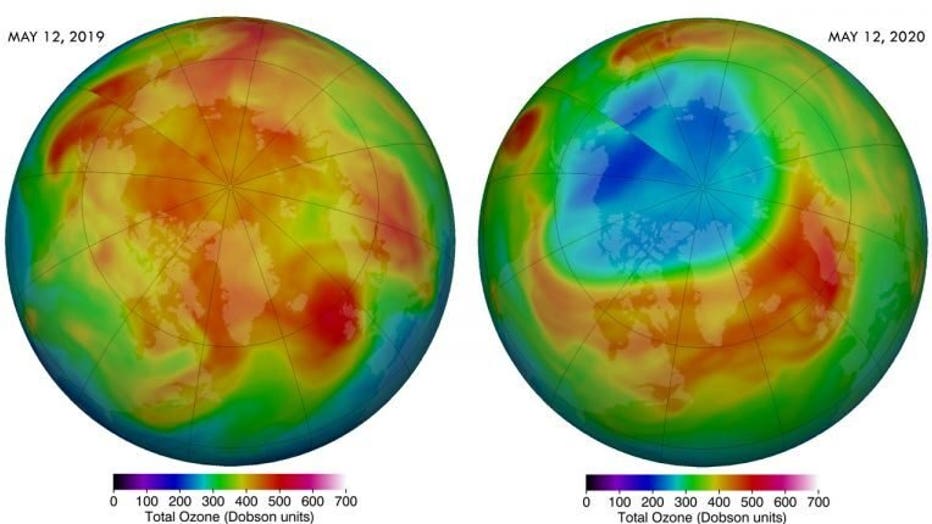

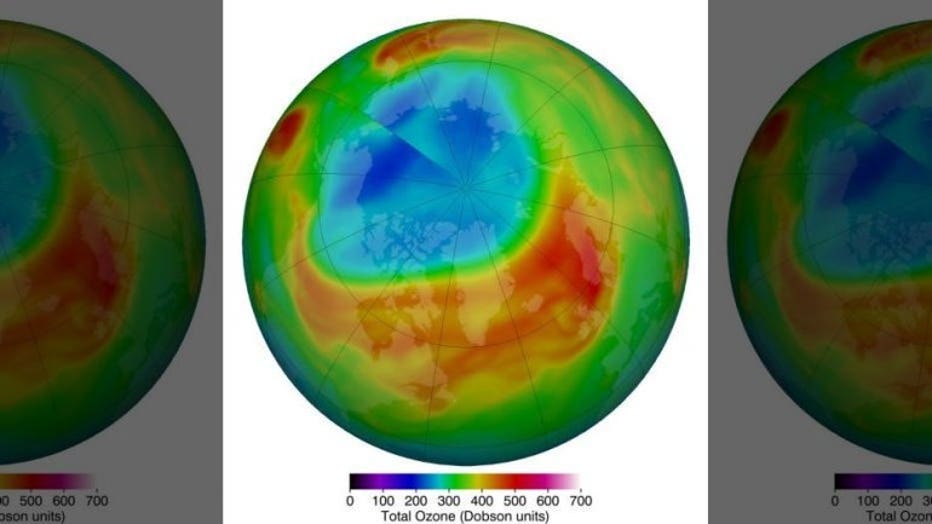

Arctic stratospheric ozone reached its record low level of 205 Dobson units, shown in blue and turquoise, on March 12, 2020 (NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center)

According to the National Weather Service, a polar vortex is described as a large area of low pressure and cold air surrounding both of Earth's poles. They typically weaken during the summer and strengthen during the winter. It's something that has "always" existed.

The ozone layer is approximately 7 to 25 miles above the Earth's surface and acts as a "sunscreen" for the planet, according to NASA. It keeps out harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun that has been linked to skin cancer, cataracts, immune system suppression and can also cause damage to plants.

NASA added that the depletion of the Arctic ozone in March was likely due to "unusually weak upper atmospheric 'wave' events from December through March." These events are similar to weather systems that are routinely seen in the lower atmosphere, but occur in the upper atmosphere "much bigger in scale."

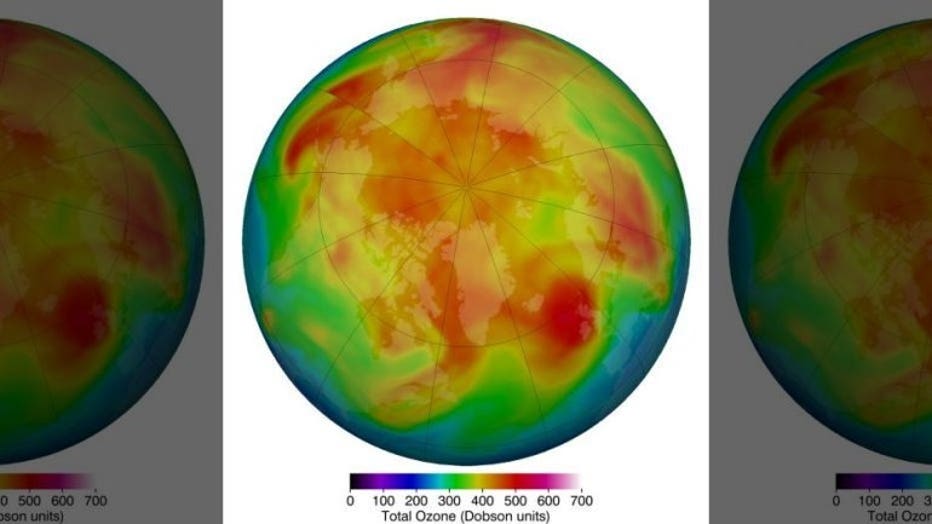

March 12, 2019, shows in reds and yellows the higher concentration of stratospheric ozone over the Arctic, which are much more typical from year to year. Usually, from December through March, waves in the upper atmosphere disrupt the circumpolar wind

These waves usually come from the lower atmosphere and "disrupt" or alter the winds that swirl around the Arctic. When that happens, the ozone is brought with them from other parts of the stratosphere.

“Think of it like having a red-paint dollop, low ozone over the North Pole, in a white bucket of paint,” said Paul Newman, chief scientist for Earth Sciences at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in a statement. “The waves stir the white paint, higher amounts of ozone in the mid-latitudes, with the red paint or low ozone contained by the strong jet stream circling around the pole.”

NASA added that the wave events were weak in December 2019 and the period from January to March 2020, preventing the ozone from other parts of the atmosphere from replenishing over the Arctic.

CAMS said they don't expect the same conditions to occur next year.